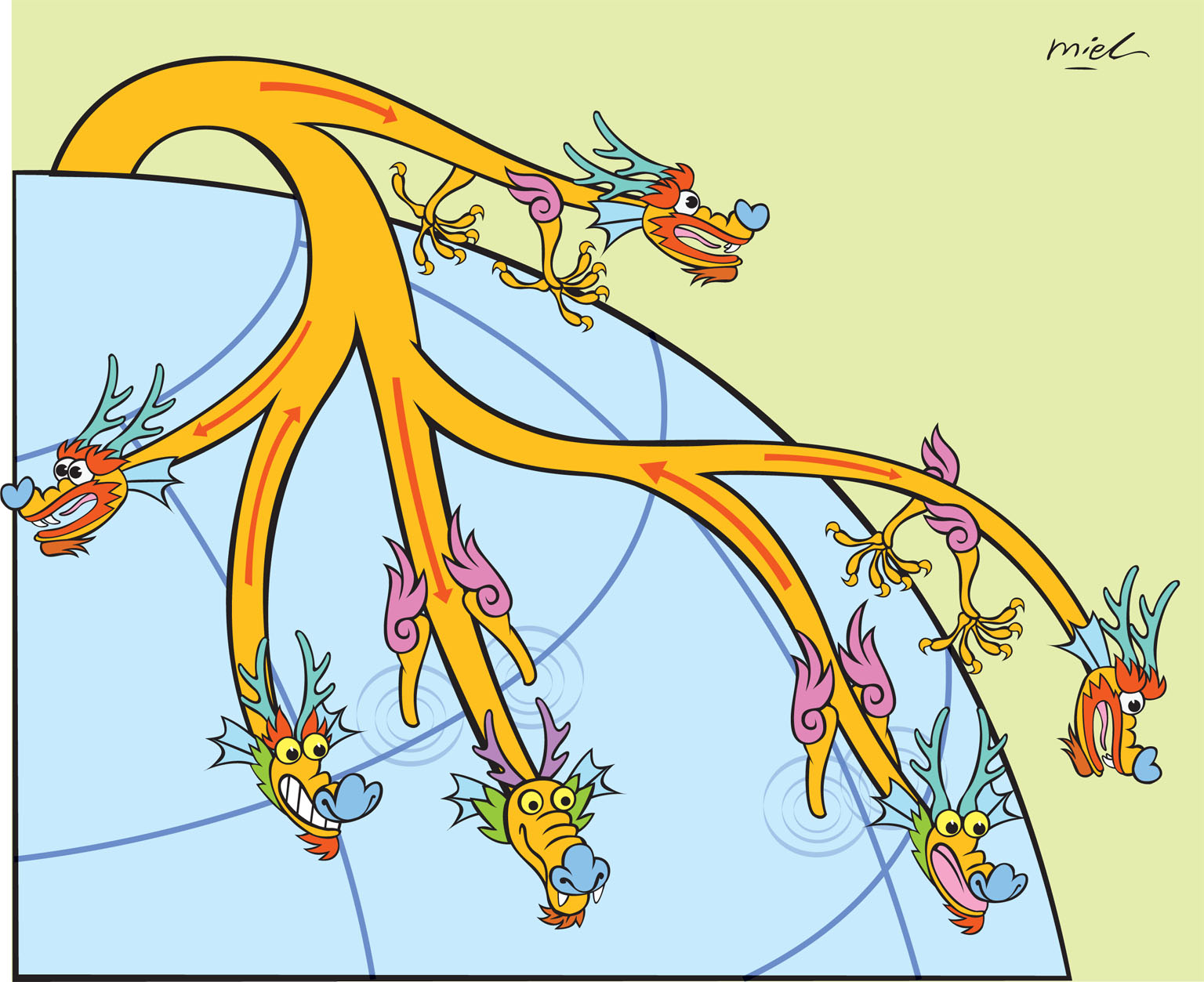

The world through the lens of Chinese supply chains

Straits Times |

ST ILLUSTRATION: MIEL

ST ILLUSTRATION: MIEL

By Parag Khanna

From the South China Sea to the Arctic to Africa, China's moves around the world aim to expand its supply chain, not impose control.

In 2010, Canada hosted the Group of Seven (G-7) finance ministers in Nunavut, the country's frigid Arctic province, home to a mere 30,000 Inuit people. Canada's "Northern Strategy" was a centrepiece of former prime minister Stephen Harper's tenure, resulting in a larger coast guard, new icebreakers, military logistics centres across the Northwest Territories, regular drone surveillance flights and a fleet of stealth snowmobiles code-named Loki. When asked why Canada was placing such strategic emphasis on the Arctic, Mr Harper responded with a simple phrase: "Use it or lose it."

There is no better expression to capture China's geopolitical manoeuvrings than "use it or lose it". In contrast to legalistic approaches that dominate Western thinking, China views the world almost entirely through the lens of supply chains.

As Chinese growth and consumption surged in the 1990s, the country became a huge importer of raw materials from countries that the West began to ignore as the Cold War ended. China is now the top trade partner of 124 countries, more than twice as many as the United States (52).

China sees New Zealand as a food supplier, Australia as an iron ore and gas exporter, Zambia as a metals hub and Tanzania as a shipping hub. Argentinian scholar Mariano Turzi calls his country a "soya bean republic" in the light of the shift in its agribusiness to serve Chinese demand. Supply and demand is the governing law of the 21st century, not sovereignty.

The South China Sea is where China's "use it or lose it" strategy is on full display. In its quest to generate a greater share of its raw materials east of strategic choke points such as the Strait of Malacca, China is deploying novel approaches to establish "facts in the water", while littoral neighbours such as the Philippines seek arbitration from international tribunals.

With an estimated 30 trillion cubic m of gas and 10 billion barrels of oil lying beneath the South China Sea, China has sent a towable oil and gas exploration rig, the Haiyang Shiyou 981, to probe in and out of Vietnamese waters near the Paracel Islands multiple times in 2014 and last year. Mr Wang Yilin, chairman of state-owned oil firm China National Offshore Oil Corporation, has called these movable deep-water rigs "strategic weapons", part of China's "mobile national sovereignty".

China's "use it or lose it" approach also involves another strategic weapon much cheaper than oil rigs or aircraft carriers: Sand. The People's Liberation Army has been installing bricks-and-mortar airstrips, lighthouses, garrisons, signals stations and administrative centres on neglected or abandoned islands in the Spratly island chain. Fiery Cross Reef has become the epicentre of what some call an "island factory", where large-scale seabed dredging and land reclamation are used to build up and connect separate shoals into larger islands. China is assuming de facto control while de jure sovereignty is arbitrated indefinitely.

The Arctic and Antarctic regions are also key geographies for China's "use it or lose it" world view. Even as China negotiates patiently to gain observer status and potentially membership in the Arctic Council (which involves everything from attempting major land purchases in Iceland to back-channel diplomacy with Norway over the fallout from awarding the Nobel Peace Prize to Chinese dissidents), it has also dangled multibillion-dollar investments to the 60,000 people of Greenland to open its uranium industry to Chinese mining companies, which colonial power Denmark presently rejects. Within the coming few years, however, Greenland could vote for independence - and find a new role as a Chinese supply-chain colony.

Antarctica, the only continent without a native human population, has also been geopolitically dormant during the past half-century, when it was governed by the de jure logic of the 1961 Antarctic Treaty, which bans any military activity or oil prospecting. That has not stopped China from sending icebreakers to clear the way for geologic surveying to determine if hundreds of billions of barrels lie beneath the ice and rock. Last year, China signed a ship refuelling agreement with Australia to facilitate these long-distance voyages of commercial colonisation.

17TH-CENTURY DUTCH, 21ST-CENTURY CHINA

Experts who compare China's 21st-century rise to that of Otto von Bismarck's Germany miss a far more appropriate historical analogy: The 17th-century Dutch. While the Spanish and Portuguese crowns were the first truly global empires, they physically subjugated (through violent conquest and even genocide) large swathes of Latin America, Africa, Asia and Oceania.

The Dutch, by contrast, operated in a less brutal and more commercial fashion. The Dutch East India Company, chartered in 1602, is considered the world's first multinational corporation that issued stocks and bonds to finance expeditions. The Dutch deployed more merchant ships (5,000) and traders (almost one million) over a 200-year period than the rest of Europe combined.

There are remarkable similarities between Amsterdam's strategy 400 years ago and Beijing's today. It is the Dutch model of infrastructure for resources that China follows, not British or French colonialism that sought to administer and socially engineer entire societies.

Though the Dutch used force in alliance with local rulers to oust the Portuguese and establish administrative control - particularly in Sri Lanka and Indonesia - the objective was to secure trading posts and harness natural resource wealth, not to conquer the world for God or country.

Two hundred years earlier, the great Ming Dynasty Admiral Zheng He's massive 15th-century "Treasure Fleet" voyages had also established China's peaceful relations with kingdoms as far as East Africa. Like Ming China, the Dutch were about trade, not territory: They were an empire of enclaves.

LARGEST MERCHANT MARINE FLEET

As with its Ming forebears and the 17th-century Dutch, China today operates the largest merchant marine fleet of more than 2,000 vessels - barges, bulk carriers, petroleum tankers and container ships - that sail all the oceans, including increasingly the Arctic.

By contrast, there are currently fewer than 100 US-flag-flying ships on the oceans.

China also builds, operates and in many cases owns critical ports and canals that underpin its growing supply-chain empire. (The Hong Kong-based company Hutchison Whampoa runs both ends of the Panama Canal.)

China has built dozens of such special economic zones (SEZs) not only inside its own borders but also across Asia, Latin America and Africa. SEZs are the commercial garrisons of a supply-chain world, enabling China to secure resources without the messy politics of colonial subjugation.

Geopolitical and economic analysts should note that even as China's resource imports and consumption slows, it will still want secure supply chains to all continents for its exports as well. China's newest SEZs from Somalia to South Africa capitalise on cheaper labour than its own and accelerate access for its textiles and manufactured goods to fast-growing markets.

In this way, China is quickly becoming the world's largest cross-border investor as measured by foreign exchange reserves, portfolio capital and foreign direct investment, with its total overseas holdings projected to reach US$20 trillion (S$27 trillion) by 2020. China's supply-chain grand strategy will therefore persist irrespective of today's economic downturn and market volatility.

In the coming decade, this competition to control supply chains is how we will see geopolitics playing out. Many people view geopolitics as being about the bending of borders. But in the 21st century, we should pay more attention to the bending of supply chains.