A New Map for America

The New York Times |

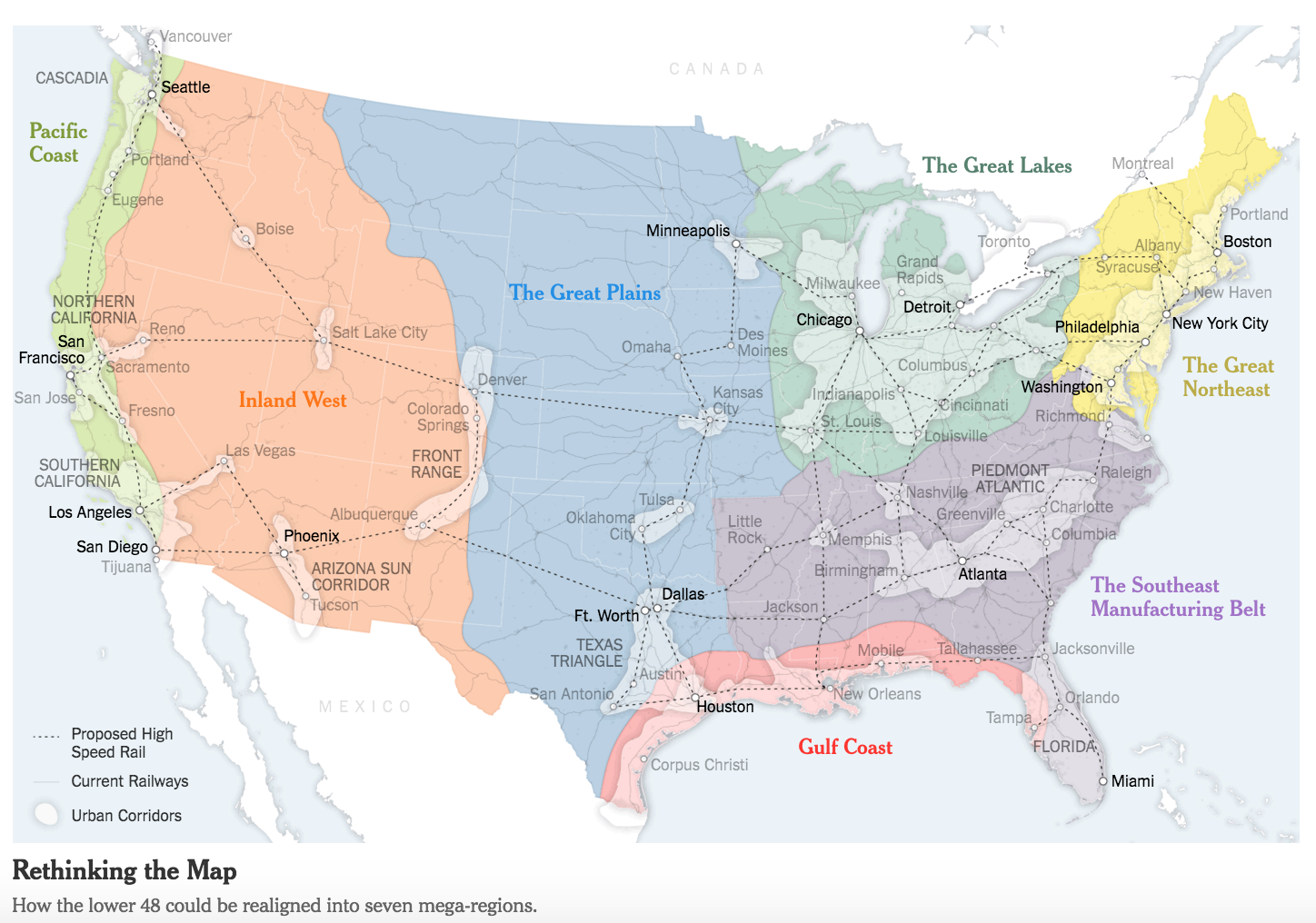

Sources: oel Kotki (boundaries and names of 7 mega-regions); Forbes Magazin; Regional Plan Association; Census Bureau; nited State High Speed Rail Association; Clare Trainor/University of Wisconsin-Madison Cartography Laboratory.

Sources: oel Kotki (boundaries and names of 7 mega-regions); Forbes Magazin; Regional Plan Association; Census Bureau; nited State High Speed Rail Association; Clare Trainor/University of Wisconsin-Madison Cartography Laboratory.

By Parag Khanna

THESE days, in the thick of the American presidential primaries, it’s easy to see how the 50 states continue to drive the political system. But increasingly, that’s all they drive — socially and economically, America is reorganizing itself around regional infrastructure lines and metropolitan clusters that ignore state and even national borders. The problem is, the political system hasn’t caught up.

America faces a two-part problem. It’s no secret that the country has fallen behind on infrastructure spending. But it’s not just a matter of how much is spent on catching up, but how and where it is spent. Advanced economies in Western Europe and Asia are reorienting themselves around robust urban clusters of advanced industry. Unfortunately, American policy making remains wedded to an antiquated political structure of 50 distinct states.

To an extent, America is already headed toward a metropolis-first arrangement. The states aren’t about to go away, but economically and socially, the country is drifting toward looser metropolitan and regional formations, anchored by the great cities and urban archipelagos that already lead global economic circuits.

The Northeastern megalopolis, stretching from Boston to Washington, contains more than 50 million people and represents 20 percent of America’s gross domestic product. Greater Los Angeles accounts for more than 10 percent of G.D.P. These city-states matter far more than most American states — and connectivity to these urban clusters determines Americans’ long-term economic viability far more than which state they reside in.

This reshuffling has profound economic consequences. America is increasingly divided not between red states and blue states, but between connected hubs and disconnected backwaters. Bruce Katz of the Brookings Institution has pointed out that of America’s 350 major metro areas, the cities with more than three million people have rebounded far better from the financial crisis. Meanwhile, smaller cities like Dayton, Ohio, already floundering, have been falling further behind, as have countless disconnected small towns across the country.

The problem is that while the economic reality goes one way, the 50-state model means that federal and state resources are concentrated in a state capital — often a small, isolated city itself — and allocated with little sense of the larger whole. Not only does this keep back our largest cities, but smaller American cities are increasingly cut off from the national agenda, destined to become low-cost immigrant and retirement colonies, or simply to be abandoned.

Congress was once a world leader in regional planning. The Louisiana Purchase, the Pacific Railroad Act (which financed railway expansion from Iowa to San Francisco with government bonds) and the Interstate System of highways are all examples of the federal government’s thinking about economic development at continental scale. The Tennessee Valley Authority was an agent of post-Depression infrastructure renewal, job creation and industrial modernization cutting across six states.

What is needed, in some ways, is a return to this more flexible, broader way of thinking. Already, efforts to coordinate metropolitan and regional planning and investment are underway, whether they are quasi-government entities like the Western High Speed Rail Alliance, which aims to link Phoenix, Denver and Salt Lake City with next-generation trains, or industry-driven groups like CG/LA Inc., which promotes public-private investment in a new national infrastructure blueprint. Ironically, even some states are warming to the idea: Regional cooperation and planning is a top item at the National Governors Association.

These are the groups that are pushing America deeper into the global economy by rethinking how the national economy functions. But they have to go it alone, because Congress still thinks in terms of states. America needs a new map.

We don’t have to create these regions; they already exist, on two levels. First, there are now seven distinct super-regions, defined by common economics and demographics, like the Pacific Coast and the Great Lakes. Within these, in addition to America’s main metro hubs, we find new urban archipelagos, including the Arizona Sun Corridor, from Phoenix to Tucson; the Front Range, from Salt Lake City to Denver to Albuquerque; the Cascadia belt, from Vancouver to Seattle; and the Piedmont Atlantic cluster, from Atlanta to Charlotte, N.C.

Federal policy should refocus on helping these nascent archipelagos prosper, and helping others emerge, in places like Minneapolis and Memphis, collectively forming a lattice of productive metro-regions efficiently connected through better highways, railways and fiber-optic cables: a United City-States of America.

Similar shifts can be found around the world. Despite millenniums of cultivated cultural and linguistic provinces, China is transcending its traditional internal boundaries to become an empire of 26 megacity clusters with populations of up to 100 million each, centered around hubs such as Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and Chongqing-Chengdu. Over time these clusters, whose borders fluctuate based on population and economic growth, will be the cores around which the central government allocates subsidies, designs supply chains and builds connections to the rest of the world.

Western countries are following suit. As of 2015, Italy’s most important political players are no longer its dozens of laconic provinces, but 14 “Metropolitan Cities,” like Rome, Turin, Milan and Florence, each of which has been legislatively merged with its surrounding municipalities into larger and more economically viable subregions.

Britain is also in the midst of an internal reorganization, with the government of Prime Minister David Cameron driving investment toward a new corridor stretching from Leeds to Liverpool known as the “Northern Powerhouse” that can become an additional economic anchor beyond London and Scotland.

What would this approach look like in America? It would start by focusing not on state lines but on existing lines of infrastructure, supply chains and telecommunications, routes that stay remarkably true to the borders of the emergent super-regions, and are most robust within the new urban archipelagos.

Connectivity isn’t just about infrastructure; it’s about strategy. It’s not just about more roads, rail lines and telecommunications — as well as manufacturing plants and data centers — but where those are placed. Getting that right is critical to getting the most out of public investment. But too often, decisions about infrastructure investment are made at the state (or even county) level, and end at the state border.

Consider the Gulf Coast arc from Houston to Tampa, an area growing on the back of the shale energy industry and agricultural exports. The ports of Corpus Christi and Tampa both received federal foreign trade zone status in the early 1980s and have been raising bridges and expanding terminals to prepare for larger ships coming through the Panama Canal — and their modernization also means accelerated export of food, oil and cars from America’s heartland. Their fates are more intertwined than Tampa’s is with Tallahassee or Corpus Christi’s is with Austin, even though they’re in the same state — and yet building out their infrastructure depends largely on the political whims of their respective state capitals. As a result, the region’s ports have built redundant facilities rather than strengthening those best suited to capitalize on new economic connections.

Nor is it just about federal policy. States need to work across borders, too. For example, instead of waging a 1980s Asian-style race to the bottom to attract low-wage auto jobs at Nissan, Honda or Toyota plants, Tennessee and Kentucky should join forces to become an advanced manufacturing hub for the global auto industry, with better cross-border infrastructure. They may end up with fewer plants, but they would be more competitive ones, especially if they could coordinate research and development through the states’ public and private universities.

Where possible, such planning should even jump over international borders. While Detroit’s population has fallen below a million, the Detroit-Windsor region is the largest United States-Canada cross-border area, with nearly six million people (and one of the largest border populations in the world). Both sides are deeply interdependent because of their automobile and steel industries and would benefit from scaling together rather than bickering over who pays for a new bridge between them. Detroit’s destiny seems almost obvious if we are brave enough to build it: a midpoint of the Chicago-Toronto corridor in an emerging North American Union.

TO make these things happen requires thinking beyond states. Washington currently provides minimal support for regional economic efforts and strategies; it needs to go much further, even at the risk of upsetting established federal-state political balances. A national infrastructure bank, if it ever gets off the ground, should have as part of its charter an obligation to ignore state lines when weighing projects to support.

Consider how parts of the Rust Belt could benefit from this approach. A Midwestern high-speed rail network that ran from Southern Illinois to Southern Michigan would not just link wealthy investment hubs like Louisville, Ky., and Columbus, Ohio; by tying in high-unemployment cities like Dayton, it would make it easier for workers to commute to where the jobs are.

Such networks would just as easily help poor and rural areas, like Appalachia. Upgraded transportation corridors between New York, Washington and Atlanta could finally lift Appalachia’s isolated and stagnant towns stretching from New York to Alabama by facilitating investment in farms and vineyards, food processing and eco-tourism.

States will continue to have an important political and regulatory function to fill. But the next president has to move beyond platitudes and implement a serious policy of leveraging new infrastructure investment from home and abroad and backing the shift toward a new urban political economy built around transportation engineering, alternative energy, digital technology and other advanced sectors.

The 21st century will not be a competition over territory, but over connectivity — and only connecting American cities will enable the United States to win the tug of war over global trade volumes, investment flows and supply chains. More than America’s military grand strategy, such an economic master plan would determine if America remained the world’s leading superpower.