Smart Cities and a Borderless World: What If Maps Revealed Infrastructure, Not Borders?

Line/Shape/Space |

By Taz Loomans

When Parag Khanna’s mother was eight months pregnant, she signed a slew of waivers to be allowed on an airplane. It turned out to be the most turbulent flight of her life, and Khanna was almost born high above the man-made borders that define the modern world.

So by coincidence or destiny, it’s fitting that Khanna grew up to be a post-border global citizen and thought leader. In the TED speaker and CNN Global Contributor’s new book, Connectography, he asks: What would it be like to live in a borderless world? He posits that through the lens of infrastructure—transportation, energy, water, sanitation, and communication—our world is increasingly connected and political borders matter less and less. “We’ve never lived in a world of solid, equal, sovereign states,” he says. “That’s always been a fiction.”

The Personal Is Political. It’s remarkable how Khanna’s personal journey reflects his theory of connectivity. “I’ve been traveling since I was born,” he says. “We spent a lot of time traveling to other countries, and then I made a career out of it.”

Khanna was born in India, grew up in Abu Dhabi and Dubai, then spent eight years in New York and completed high school as an exchange student in Germany. After graduating from Georgetown, he lived in New York and Geneva, where he worked for the World Economic Forum before earning his PhD at the London School of Economics. Khanna and his family now live in Singapore. With such an international life, it’s easy to understand why he sees a world empowered by infrastructure and supply chains, not borders.

“When I was traveling in Central Asia, where practically every country ends with a ‘stan,’ I started to notice that the instrument of power wasn’t the tank or the aircraft carrier, but the roads, the railways, and the construction crews,” he says.

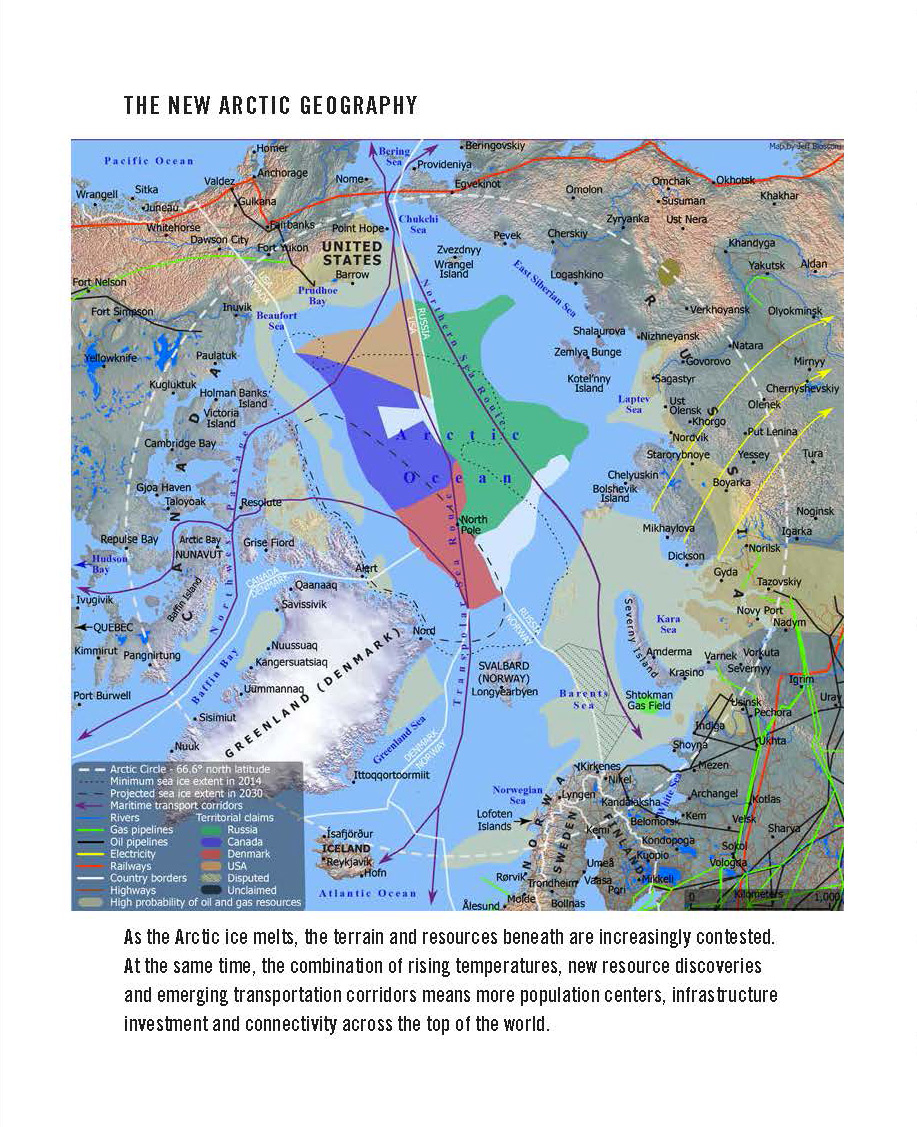

Today, most people see the world with distinct countries drawn on a map and clear borders between them. But Khanna points out that, “If you saw maps that only show infrastructure rather than borders, you wouldn’t think borders are more important than infrastructure. In fact, infrastructures are way more important than borders. Infrastructure connects people, resources, goods, ideas, finance, and capital.

“For example,” Khanna continues, “you can look at the volume of trade and capital and the number of migrants crossing borders. You can look at the number of business travelers, flows of technologies, and the way natural resources can move from one point of the world to any other point. Every conceivable data point—without any exception at all—in every single category of human existence, connectivity is accelerating and is far greater now than in any other point in history.”

Politicians With Borders. Despite this movement toward disappearing borders, xenophobic and protectionist politics persist, such as with Republican presidential front-runner Donald Trump calling for a wall on the U.S.–Mexico border.

“Mexico must pay for the wall,” Trump said, “and, until they do, the United States will, among other things: impound all remittance payments derived from illegal wages, increase fees on all temporary visas issued to Mexican CEOs and diplomats, increase fees on all border crossing cards of which we issue about one million to Mexican nationals each year, increase fees on all NAFTA worker visas from Mexico, and increase fees at ports of entry to the United States from Mexico.”

But Khanna isn’t worried about the rhetoric of conservative politicians. “I’m not really all that concerned that Donald Trump wants to put up a wall on the U.S.–Mexico border,” he says. “We obsess a lot about conservative politics, but if such people ever come to power, the realities of interdependence often temper their harsh positions.”

The reality, Khanna says, is an increased flow between countries, not a restricted flow. Despite alarmist politics, the world is still trending toward radical connectivity. For example, people look at Europe and think that it is tightening its borders due to security and economic concerns. But Khanna points out that, “Never, in the history of Europe, have more people entered Europe in one year than they have in 2015. We should look at what people do, not just what they say.”

Politicians like Trump claim immigrants are hurting their country’s economy, but Khanna disagrees: “America needs immigrants as entrepreneurs; it needs immigrants to pick cotton and almonds, to take care of the elderly, to be bus drivers and doctors. And Europe needs more immigrants than America does.”

But the economy isn’t the only reason some politicians want to close borders. With terrorist attacks on the rise, security is an ever-present concern for governments. Khanna admits that “tightening borders can potentially stop specific instances of terrorist attacks,” he says. “But now we are in a situation where many terrorists are citizens of the same country they attack or have Western passports that allow them to travel seamlessly across borders, so it is too late to stop those kinds of flows. In any case, domestic terrorism accounts for more than 90 percent of terrorist attacks, so it’s not clear how tightening borders would help.”

Bringing Down Barriers. Instead of clamping down on borders, Khanna proposes doing the opposite. “Unlocking flows of any kind, except for say, pandemics and terrorists, is generally a good thing,” Khanna says. “Every single important region in the world is moving toward reducing visa requirements, barriers to digital technologies, flows of investment capital and labor, and are building more cross-border infrastructure. Even the most dangerous parts of the world are doing this.”

But how exactly do citizens go with the flow, as it were, and embrace a borderless world? Slowly, says Khanna: “You don’t bring down borders at once. You bring them down in different places at different times.” It happens country by country and region by region. “The way you build a borderless world of peace and equilibrium,” he says, “is by each pair of nations improving their stability and relations between them and by expanding that circle bit by bit.”

Khanna insists that the idea of a borderless world isn’t as radical as it sounds. It’s just a matter of seeing the world as a network rather than static lines on a map. He’s hoping that strategists in Washington take note of Connectography and start thinking more in terms of a connected world instead of a divided one.