There are better governments than America’s — it’s time to learn from them

LinkedIn Pulse |

America’s democracy remorse began well before the 2016 election that resulted in Donald Trump’s shocking victory. A 2014 Gallup survey found that 65 percent of Americans were dissatisfied with their system of government. On the eve of the election, a Stanford/Survey Monkey poll found that 40 percent of respondents have “lost faith in American democracy.” Maybe the best way to save American democracy would be to have less of it, to balance it out with better ways of structuring institutions, devising policy and managing society.

In researching my new book Technocracy in America, I studied all the governments that rank higher than the U.S. in socio-economic metrics such as life expectancy and median income, as well as political indicators such as low corruption, high trust in government and governance effectiveness. Fortunately, I’ve lived in several of them (and spent extensive time in most of them) so can attest to their higher quality of life than what the average American experiences. Since no one country has the perfect political system, I’ve amalgamated the best practices in how to structure the executive branch, legislature and judiciary into a model I call “direct technocracy.”

If America wants to have the most respected political system in the 21st century, it needs to graduate from indirect democracy to direct technocracy.

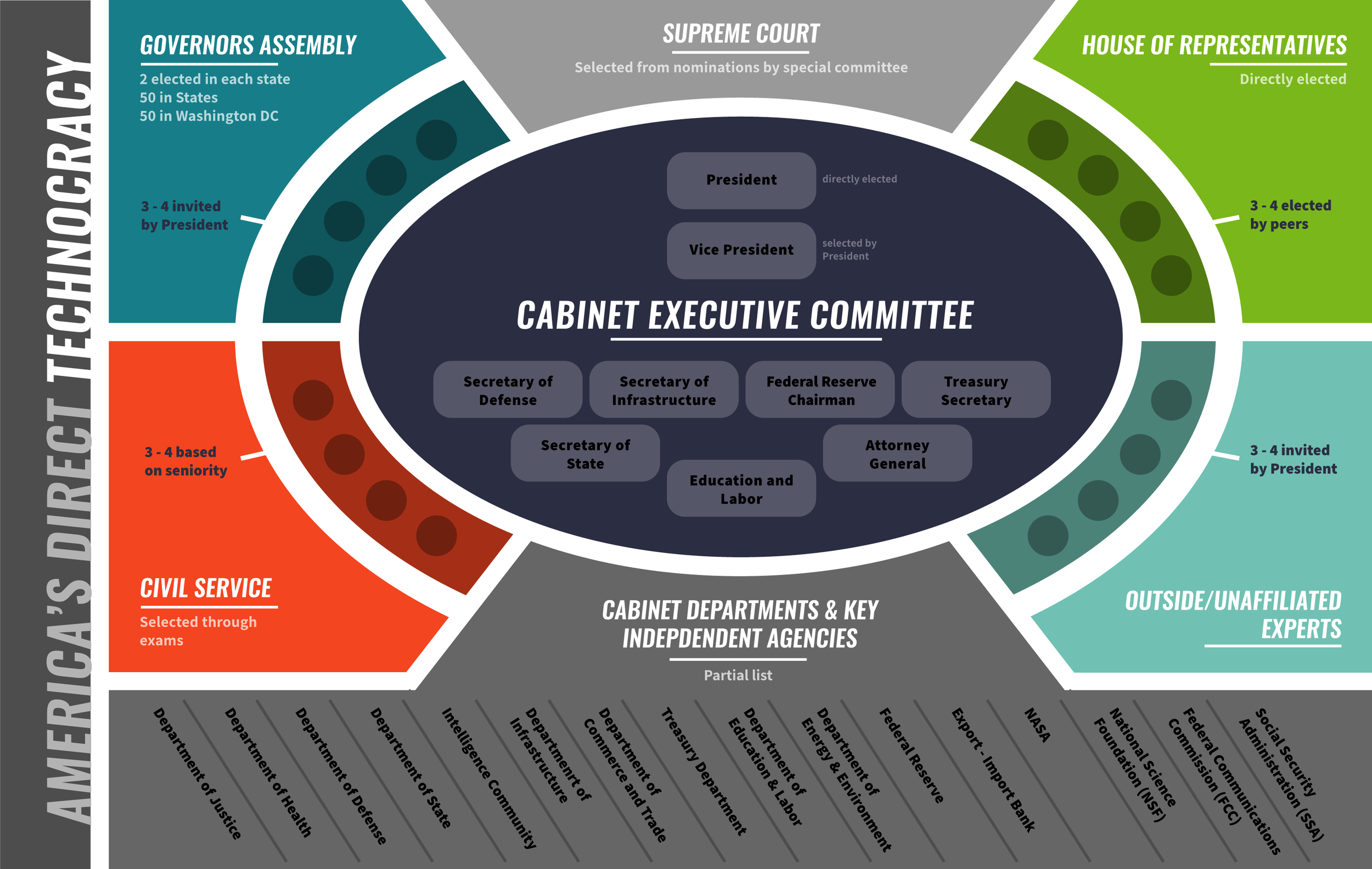

First, the White House should be occupied not by one person but a committee of a half-dozen leaders who make consensus-based decisions on national priorities. Switzerland, the world’s oldest and most respected democracy, has such a “collective presidency.” In fact, it is a true “team of rivals” representing elected legislators from four different parties who rotate the chairmanship each year. China’s Politburo Standing Committee also has seven members elected by the Communist Party based on their merit and experience. Neither country has “Friends of [fill in the blank]” running anything, nor do the individuals operate in silos like America’s cabinet. They are a team in which all members have skin in the game and juggle complex demands together. Seven heads are better than one.

If America were to initiate such a collective presidency, it would be anchored by a directly elected president. Let’s get rid of that anachronistic electoral college, please. Alongside the vice president, other members of this executive committee could be chosen from from the top ranks of government agencies and outside experts, and even sitting members of Congress. Nothing prohibits Congressmen from taking on roles in the executive branch, and indeed this might be the surest way to build bridges and avoid political gridlock.

The Constitution also says nothing about political parties, but it is clear that all countries in the world that rank higher than America on the Quality of Democracy index have more than just two of them. Indeed, all such multi-party parliamentary systems form coalition governments in which governing parties have to make good on their promises to the electorate or risk having government dissolved, snap elections called, and getting tossed out within 90 days. In high-quality democracies, there are far fewer safe seats than in America’s gerrymandered duopoly.

The legislative branch needs at least one more big change: Abolishing the Senate. Such upper house bastions of privilege become more irrelevant in direct proportion to how many of them are former members of the House of Representatives. In the good old days, Senators were mostly former governors; they had real experience running large state bureaucracies and budgets. Today the Senate is mostly former Reps, and hence the Senate seems to exist for the same reason as the House: to squabble over procedures and fundraise for reelection.

Instead, the entire Senate should be replaced by what I call the “Assembly of Governors.” Rather than each state having two senators, it should have two governors—either running on a joint ticket, or with the two most popular candidates being chosen. After the election, one works in the state capital and the other in Washington coordinating priorities and agendas and sharing successful policies with their peers from other states. Unlike squabbling senators, governors get along extremely well with each other and overwhelmingly favor cross-border projects that enhance the national interest.

There are many other major institutional fixes the federal government needs. The Supreme Court, for example, should have justices who serve one term of ten years and are selected based not on how wedded they are to strict constructionist doctrine but rather their willingness to propose amendments to adapt the Constitution to the times. Germany, for example, regularly amends its constitution (the “Basic Law” known as the Grundgesetz) to recognize more national languages, increase the mandate for social services provision, re-regulate the role of police or strengthen protection of privacy.

Equally important, America needs to restore the deep bench of the civil service that built the modern American superpower a century ago, managing our railways, highways to social security. A strong civil service gets things done even when elected politicians do nothing. The top-ranked government bureaucracies are rated according to their meritocratic hiring and promotion, capacity for collecting and analyzing data, and the number of advanced degree holders employed. Today it is Singapore’s civil service that ranks highest in the world both in terms of its capacity and bureaucratic autonomy. Rather than just debating the role of “fake news” on social media, Singapore’s officials canvas Facebook and other platforms to get a better understanding of the needs of the public and constantly adjust policies accordingly.

Each of these proposals is mapped out in more detail in Technocracy in America, and some are embedded in the organizational chart (below).

America doesn’t have to continue to degenerate into a money and personality driven political system. Its leaders can be selected meritocratically rather than by patronage networks, and its policies can be designed in a utilitarian way rather than by special interests. America’s democracy could once again be the world’s greatest if there were a little less of it.

America’s democracy remorse began well before the 2016 election that resulted in Donald Trump’s shocking victory. A 2014 Gallup survey found that 65 percent of Americans were dissatisfied with their system of government. On the eve of the election, a Stanford/Survey Monkey poll found that 40 percent of respondents have “lost faith in American democracy.” Maybe the best way to save American democracy would be to have less of it, to balance it out with better ways of structuring institutions, devising policy and managing society.

In researching my new book Technocracy in America, I studied all the governments that rank higher than the U.S. in socio-economic metrics such as life expectancy and median income, as well as political indicators such as low corruption, high trust in government and governance effectiveness. Fortunately, I’ve lived in several of them (and spent extensive time in most of them) so can attest to their higher quality of life than what the average American experiences. Since no one country has the perfect political system, I’ve amalgamated the best practices in how to structure the executive branch, legislature and judiciary into a model I call “direct technocracy.”

If America wants to have the most respected political system in the 21st century, it needs to graduate from indirect democracy to direct technocracy.

First, the White House should be occupied not by one person but a committee of a half-dozen leaders who make consensus-based decisions on national priorities. Switzerland, the world’s oldest and most respected democracy, has such a “collective presidency.” In fact, it is a true “team of rivals” representing elected legislators from four different parties who rotate the chairmanship each year. China’s Politburo Standing Committee also has seven members elected by the Communist Party based on their merit and experience. Neither country has “Friends of [fill in the blank]” running anything, nor do the individuals operate in silos like America’s cabinet. They are a team in which all members have skin in the game and juggle complex demands together. Seven heads are better than one.

If America were to initiate such a collective presidency, it would be anchored by a directly elected president. Let’s get rid of that anachronistic electoral college, please. Alongside the vice president, other members of this executive committee could be chosen from from the top ranks of government agencies and outside experts, and even sitting members of Congress. Nothing prohibits Congressmen from taking on roles in the executive branch, and indeed this might be the surest way to build bridges and avoid political gridlock.

The Constitution also says nothing about political parties, but it is clear that all countries in the world that rank higher than America on the Quality of Democracy index have more than just two of them. Indeed, all such multi-party parliamentary systems form coalition governments in which governing parties have to make good on their promises to the electorate or risk having government dissolved, snap elections called, and getting tossed out within 90 days. In high-quality democracies, there are far fewer safe seats than in America’s gerrymandered duopoly.

The legislative branch needs at least one more big change: Abolishing the Senate. Such upper house bastions of privilege become more irrelevant in direct proportion to how many of them are former members of the House of Representatives. In the good old days, Senators were mostly former governors; they had real experience running large state bureaucracies and budgets. Today the Senate is mostly former Reps, and hence the Senate seems to exist for the same reason as the House: to squabble over procedures and fundraise for reelection.

Instead, the entire Senate should be replaced by what I call the “Assembly of Governors.” Rather than each state having two senators, it should have two governors—either running on a joint ticket, or with the two most popular candidates being chosen. After the election, one works in the state capital and the other in Washington coordinating priorities and agendas and sharing successful policies with their peers from other states. Unlike squabbling senators, governors get along extremely well with each other and overwhelmingly favor cross-border projects that enhance the national interest.

There are many other major institutional fixes the federal government needs. The Supreme Court, for example, should have justices who serve one term of ten years and are selected based not on how wedded they are to strict constructionist doctrine but rather their willingness to propose amendments to adapt the Constitution to the times. Germany, for example, regularly amends its constitution (the “Basic Law” known as the Grundgesetz) to recognize more national languages, increase the mandate for social services provision, re-regulate the role of police or strengthen protection of privacy.

Equally important, America needs to restore the deep bench of the civil service that built the modern American superpower a century ago, managing our railways, highways to social security. A strong civil service gets things done even when elected politicians do nothing. The top-ranked government bureaucracies are rated according to their meritocratic hiring and promotion, capacity for collecting and analyzing data, and the number of advanced degree holders employed. Today it is Singapore’s civil service that ranks highest in the world both in terms of its capacity and bureaucratic autonomy. Rather than just debating the role of “fake news” on social media, Singapore’s officials canvas Facebook and other platforms to get a better understanding of the needs of the public and constantly adjust policies accordingly.

Each of these proposals is mapped out in more detail in Technocracy in America, and some are embedded in the organizational chart (below).

America doesn’t have to continue to degenerate into a money and personality driven political system. Its leaders can be selected meritocratically rather than by patronage networks, and its policies can be designed in a utilitarian way rather than by special interests. America’s democracy could once again be the world’s greatest if there were a little less of it.