Crazy and rich … but also generous

OZY |

Several notable strands of commentary have emerged from the hit film Crazy Rich Asians, which has been taking cinemas by storm for several weeks. Many have taken pride in the film’s all-Asian cast, while others have marveled at the dazzling confidence radiated by the modern setting of Singapore. Facebook star Nuseir Yassin, known for his thoughtful one-minute Nas Daily videos, recently visited Singapore, making a splash with one episode titled “Why I Hate Singapore.” The answer? Because he’s jealous that it’s practically perfect. But there’s sharp inequality embedded in cities like Singapore — cities of staggering wealth built by temporarily imported low-wage immigrant labor.

A common theme that emerges is one of Asia’s millennials being in a state of hyper-rich materialist overdrive with their Jimmy Choos, Ferraris and $40 million weddings. Yet masked by glitzy Hollywood portraits and corporate reports gushing about Asia’s newly minted billionaires is the reality that Asian culture prizes community over individual and has deep traditions of the generous sharing of wealth.

Several notable strands of commentary have emerged from the hit film Crazy Rich Asians, which has been taking cinemas by storm for several weeks. Many have taken pride in the film’s all-Asian cast, while others have marveled at the dazzling confidence radiated by the modern setting of Singapore. Facebook star Nuseir Yassin, known for his thoughtful one-minute Nas Daily videos, recently visited Singapore, making a splash with one episode titled “Why I Hate Singapore.” The answer? Because he’s jealous that it’s practically perfect. But there’s sharp inequality embedded in cities like Singapore — cities of staggering wealth built by temporarily imported low-wage immigrant labor.

A common theme that emerges is one of Asia’s millennials being in a state of hyper-rich materialist overdrive with their Jimmy Choos, Ferraris and $40 million weddings. Yet masked by glitzy Hollywood portraits and corporate reports gushing about Asia’s newly minted billionaires is the reality that Asian culture prizes community over individual and has deep traditions of the generous sharing of wealth.

One of the tenets of Confucianism, for example, is filial piety, not only respect of but also deference to elders — something on full display in the movie. For decades, Singapore has been the pioneer of subsidized homeownership, especially multigenerational housing that allows for extended families to remain under one roof.

Rising economic inequality worldwide threatens to weaken the social solidarity that is a foundation of a strong national ethos. This phenomenon appears to be tearing apart Western societies more than Asian ones at the moment, but no nation is immune, and Asia’s newly rich need to bear that in mind. Can Asia’s tycoons and upwardly mobile retain their trademark communal solidarity amid rapid economic growth and breakneck urbanization?

While Western philanthropists and charities grab headlines for their record-breaking donations to causes, Asians’ engagement with their social challenges unfortunately receives far less attention. Indeed, charity is enshrined in the teachings of the Buddha and in the Quran but is less systematized and publicized than in the West. According to the World Giving Index, since 2014 the country with the most consistently high rate — 90 percent — of charitable giving is also one of the poorest, Myanmar, thanks to its devout Buddhist beliefs. Similarly, owing to the principle of zakat, an alms tax that constitutes mandatory giving and is one of the five pillars of Islam, nearly 90 percent of Arab Gulf citizens made charitable donations in 2016.

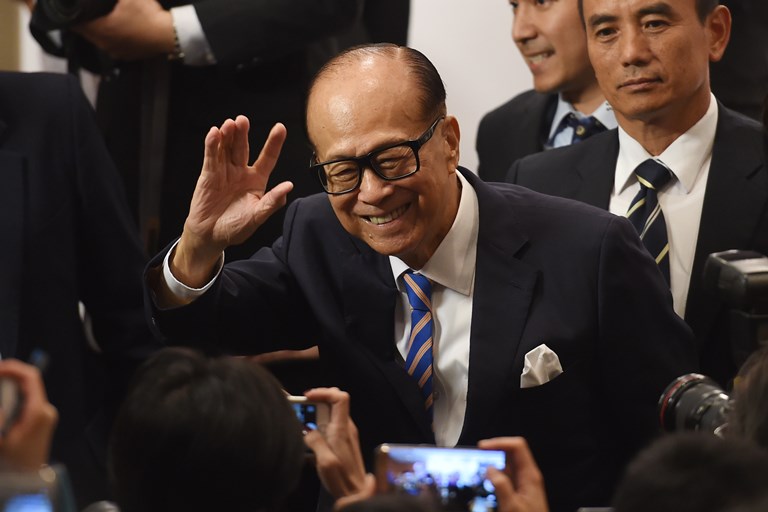

From Li Ka-shing to Prince Alwaleed bin Talal, some of Asia’s most high-profile billionaires have endowed professorships and centers devoted to their region’s affairs, their names adorning buildings at leading American and European universities. At home, however, cultural traditions encourage them to give discreetly — humbly. What is changing is both the scale of giving and its formality, with charity becoming more formalized and visible to inspire others and generate greater impact.

One of the tenets of Confucianism, for example, is filial piety, not only respect of but also deference to elders — something on full display in the movie. For decades, Singapore has been the pioneer of subsidized homeownership, especially multigenerational housing that allows for extended families to remain under one roof.

Rising economic inequality worldwide threatens to weaken the social solidarity that is a foundation of a strong national ethos. This phenomenon appears to be tearing apart Western societies more than Asian ones at the moment, but no nation is immune, and Asia’s newly rich need to bear that in mind. Can Asia’s tycoons and upwardly mobile retain their trademark communal solidarity amid rapid economic growth and breakneck urbanization?

While Western philanthropists and charities grab headlines for their record-breaking donations to causes, Asians’ engagement with their social challenges unfortunately receives far less attention. Indeed, charity is enshrined in the teachings of the Buddha and in the Quran but is less systematized and publicized than in the West. According to the World Giving Index, since 2014 the country with the most consistently high rate — 90 percent — of charitable giving is also one of the poorest, Myanmar, thanks to its devout Buddhist beliefs. Similarly, owing to the principle of zakat, an alms tax that constitutes mandatory giving and is one of the five pillars of Islam, nearly 90 percent of Arab Gulf citizens made charitable donations in 2016.

From Li Ka-shing to Prince Alwaleed bin Talal, some of Asia’s most high-profile billionaires have endowed professorships and centers devoted to their region’s affairs, their names adorning buildings at leading American and European universities. At home, however, cultural traditions encourage them to give discreetly — humbly. What is changing is both the scale of giving and its formality, with charity becoming more formalized and visible to inspire others and generate greater impact.

Ninety-year-old Li Ka-shing, Hong Kong’s richest man. SOURCE ANTHONY WALLACE/AFP/GETTY

Between 2010 and 2016, China’s top 100 philanthropic donors tripled the size of their commitments to $4.6 billion. No single Asian country has as vast a demand for welfare as India. Gandhi influenced an early generation of Indian industrialists such as the Tata and Godrej families to donate 10 percent or more of their annual earnings to a range of causes such as education. More recently, a far larger set of India’s wealthy has stepped up, with charitable donations rising sixfold between 2010 and 2016, overtaking foreign sources in volume. India has long been considered the NGO capital of the world, given an estimated 2.5 million civil society organizations active across the social, health and religious domains.

It’s worth noting that Asian philanthropy does and will not follow the same path as in the West, owing to concern over the trustworthiness of civil society groups that lack substantial track records and oversight. That’s why most Asian billionaires (with the exception of some Arabs and Indians) don’t jump to sign on to Bill Gates and Warren Buffett’s Giving Pledge to donate most of their wealth. Instead, they invest in operational charities. The Ayala Foundation in the Philippines, for example, has focused on programs in education, youth leadership, arts and culture since the 1960s. In China, 46 of the country’s wealthiest 200 people have established such foundations.

Given the importance of education in almost all of Asia’s rags-to-riches stories, it is no surprise that spreading and enhancing educational opportunities is a leading focus of philanthropists like Abdulla Ahmad al-Ghurair, founder of Mashreq Bank, who has donated $1.1 billion to educational causes. Azim Premji, chairman of Wipro, has given $8 billion to charities, and his eponymous foundation focuses primarily on improving rural education. Tencent co-founder Charles Chen left the company in 2013 to devote himself full time to a $320 million fund for transformational ideas in education and gave $300 million to upgrade the liberal arts–focused Wuhan College.

But all that said, this new spotlight on Asia’s wealth has also shined a much-needed spotlight on Asia’s less admirable extremes. India, Pakistan and the Philippines have millions of homeless people and street children. Sri Lanka, Mongolia and Kazakhstan have among the world’s highest suicide rates. Porous borders and fragile societies also help explain why Asia’s human trafficking from Saudi Arabia through Pakistan and India and across Southeast Asia surpasses the rest of the world by a wide margin. Wealthy and conscientious Asians need to do much more to address the consequences of poverty, inequality and social stress. Let’s hope that all the newly minted Crazy Rich Asians appreciate this.

Parag Khanna is author of Connectography (2016), among several other books. His latest book, The Future is Asian, will be published in February 2019 by Simon & Schuster.

Ninety-year-old Li Ka-shing, Hong Kong’s richest man. SOURCE ANTHONY WALLACE/AFP/GETTY

Between 2010 and 2016, China’s top 100 philanthropic donors tripled the size of their commitments to $4.6 billion. No single Asian country has as vast a demand for welfare as India. Gandhi influenced an early generation of Indian industrialists such as the Tata and Godrej families to donate 10 percent or more of their annual earnings to a range of causes such as education. More recently, a far larger set of India’s wealthy has stepped up, with charitable donations rising sixfold between 2010 and 2016, overtaking foreign sources in volume. India has long been considered the NGO capital of the world, given an estimated 2.5 million civil society organizations active across the social, health and religious domains.

It’s worth noting that Asian philanthropy does and will not follow the same path as in the West, owing to concern over the trustworthiness of civil society groups that lack substantial track records and oversight. That’s why most Asian billionaires (with the exception of some Arabs and Indians) don’t jump to sign on to Bill Gates and Warren Buffett’s Giving Pledge to donate most of their wealth. Instead, they invest in operational charities. The Ayala Foundation in the Philippines, for example, has focused on programs in education, youth leadership, arts and culture since the 1960s. In China, 46 of the country’s wealthiest 200 people have established such foundations.

Given the importance of education in almost all of Asia’s rags-to-riches stories, it is no surprise that spreading and enhancing educational opportunities is a leading focus of philanthropists like Abdulla Ahmad al-Ghurair, founder of Mashreq Bank, who has donated $1.1 billion to educational causes. Azim Premji, chairman of Wipro, has given $8 billion to charities, and his eponymous foundation focuses primarily on improving rural education. Tencent co-founder Charles Chen left the company in 2013 to devote himself full time to a $320 million fund for transformational ideas in education and gave $300 million to upgrade the liberal arts–focused Wuhan College.

But all that said, this new spotlight on Asia’s wealth has also shined a much-needed spotlight on Asia’s less admirable extremes. India, Pakistan and the Philippines have millions of homeless people and street children. Sri Lanka, Mongolia and Kazakhstan have among the world’s highest suicide rates. Porous borders and fragile societies also help explain why Asia’s human trafficking from Saudi Arabia through Pakistan and India and across Southeast Asia surpasses the rest of the world by a wide margin. Wealthy and conscientious Asians need to do much more to address the consequences of poverty, inequality and social stress. Let’s hope that all the newly minted Crazy Rich Asians appreciate this.

Parag Khanna is author of Connectography (2016), among several other books. His latest book, The Future is Asian, will be published in February 2019 by Simon & Schuster.