A Second Tour Through the ‘Second World’

World Politics Review |

By Parag Khanna

In the 1960s, University of Michigan scholar AFK Organski predicted that a populous, industrious China would rise in the East to challenge America as the world's paramount power, and that the U.S. and Soviet Union would ally against China despite the communist allegiance shared by the PRC and USSR. Fifty years later, we can be increasingly certain that Organski was impressively ahead of his time with this prediction. Of course, the Soviet Union no longer exists and China is an authoritarian capitalist rather than communist state. But Organski calculated how China would eventually dwarf Russia in demographic and economic might, forcing Russia into the West's arms. What we will witness in the coming decade or two is the converse of 1972: Instead of America wresting China from the Soviet orbit, the West will have to rescue Russia from its suicidal embrace of China.

How could Organski make such a prediction while China was still very much a backwards, agrarian country, self-absorbed in post-Civil War political convulsions? The answer is his power transition theory, which specifies that rising regional hegemons and declining global ones tend to go to war in the strategic geographies where they overlap and intersect. The cost-benefit analysis on the part of the rising and declining powers is intensely subjective and psychological. A hegemon could unilaterally abandon its overseas commitments and retrench, but that would only accelerate the speed with which competitors ambitiously race to fill the resulting power vacuum, while potentially spurring the main challenger to launch a pre-emptive strike.

Today, power transition theory is considered a pillar of academic geopolitics, the science of long-term change in world affairs. The best analogy to geopolitics is climatology, which captures the subtle changes in our ecosystem over time, and examines how they affect the human-environmental equilibrium. By contrast, the study of international relations is mere meteorology, the daily weather forecast.

The insights generated from geopolitical schools of thought give us enormous foresight into global trends. And for better or worse, they support the argument that the global power structure continues to rapidly diffuse away from American hegemony toward a post-American world. Not only are there already other centers of gravity in the global system, such as China and the European Union, which undermine American dominance, but a belt of several dozen second-world countries is also reshaping diplomacy, region by region and issue by issue. This diffusion is as inevitable as climate change.

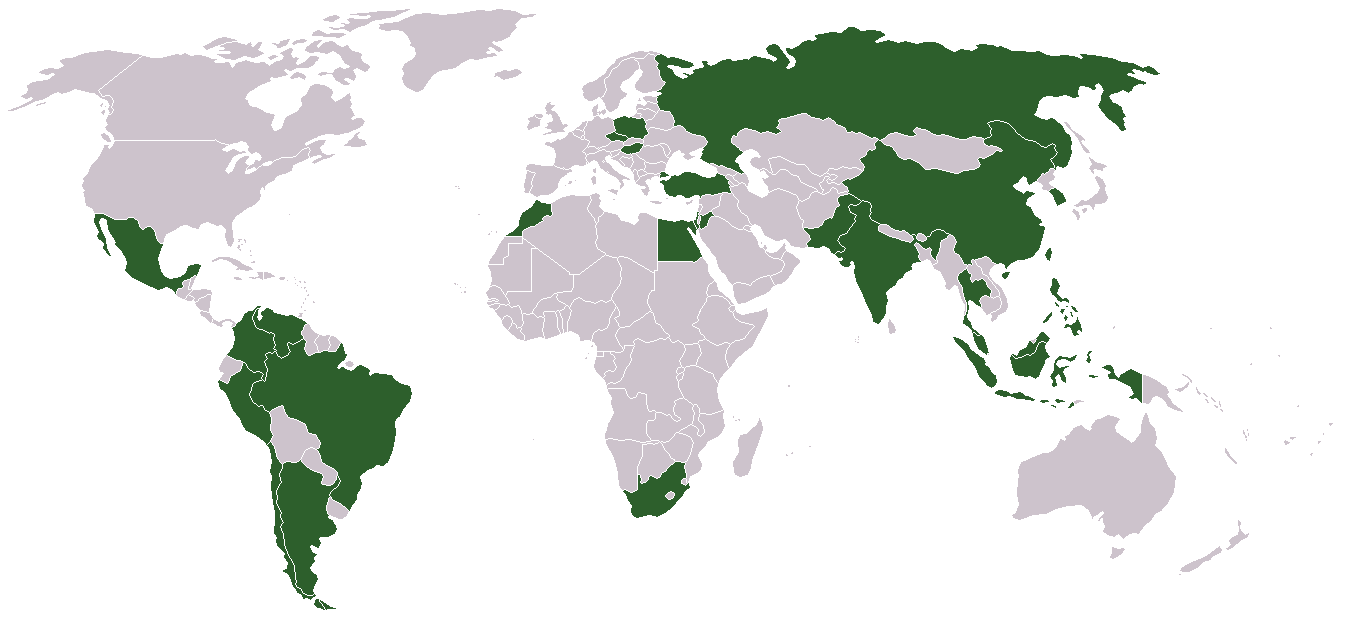

Five years ago, I spent 24 months traveling non-stop through today's aspiring regional hegemons and swing states. My 40-nation itinerary included states ranging from Ukraine and Turkey to Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, from Venezuela and Brazil to Libya, Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Syria, from India, Malaysia, Indonesia and Vietnam to, of course, China. Along the way, I witnessed smart second-world countries practicing multi-alignment, selectively engaging with the U.S., EU, and China in ways that best suit their own interests, in order to get as much as possible while giving the least in return. In a world where decisions are no longer routed through Washington, London or Moscow, the axes and alliances emerging across second-world countries, and the deepening regionalism taking hold in regional clusters, are as important to the future world order as the decisions of the superpowers.

Since the end of the Cold War, a number of events have been cited to suggest the durability of American unipolarity, as well as to challenge assertions of America's relative decline. First was the obvious absence of a peer competitor as well as the increasing frequency of American interventions abroad in the immediate aftermath of the Soviet Union's collapse. Then came the aggressive response to Sept. 11, which brought impressively quick initial victories in Afghanistan and Iraq. The world, and especially the so-called "Axis of Evil," was meant to be put on notice. Even the global financial crisis has been used as an example of how only the U.S. could have convened the world's leading powers so quickly to confront such systemic economic risks.

All of these events, however, have proven ephemeral palliatives. America's failures in the greater Middle East are plain for the world to see. In particular, second-world countries are rapidly moving away from dependence on the U.S. for political legitimacy and economic growth.

Today, there are ever more instances we can point to as illustrations of the increasingly non-American character of global power dynamics. The Brazil-Turkey initiative that could potentially reopen diplomatic channels between the West and Iran over the latter's nuclear program has been one of the most attention-grabbing recent examples. Another is the make-or-break role that China, India, and Brazil played at the Copenhagen climate negotiations in December 2009. To many observers, Copenhagen was important simply because it happened, demonstrating a global commitment to a global process and the relevance of the United Nations. But the outcome of Copenhagen was far more profound in demonstrating how no global climate deal is possible on American or Western terms alone.

Most fundamentally, the global financial crisis beginning in 2008 speaks to the long-term reality of a post-American world, since it is far less a global crisis than a Western one. With growth in Western economies hovering in the low single digits, it is a safe bet that about two-thirds or more of the world's economic growth in the coming decade will occur in emerging markets. Furthermore, not only the rate of economic growth, but the types of economic systems achieving that growth are quite un-American. Instead of laissez-faire capitalism, it is state capitalism that has propelled China, Russia, and the Persian Gulf states. Certainly Brazil and India are fast-growing democracies, but neither they nor the U.S. can claim a democratic monopoly on long-term economic growth potential.

One of the structural trends underpinning the continued diffusion of power away from America is the growing regionalization of world politics. Regional anchors from Brazil to Saudi Arabia to China have sponsored a deepening integration -- globalization within regions -- that politicians, scholars and the media have all been slow to pick up on. Regional organizations have evolved considerably in recent years. In South America, the tepid Mercosur arrangement of a decade ago has blossomed into the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR), and in the Far East, the East Asian Community is similarly heading in the direction of an Asian Union. The Gulf Cooperation Council is moving toward a common currency and undertaking thousands of miles of cross-border rail linkages. Summits between Latin, Arab, Asian and African regional groups are where the commercial and diplomatic ties among second-world countries are forged. The future consists as much of inter-regional relations as international relations.

It is easy to critique the immaturity of some emerging powers. India is still unable to tame South Asia, and exists in a state of semi-permanent hostility and tension with neighbors such as Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka. China remains untested and untrusted when it comes to mediating the future of the South China Sea, whose perimeter and under-sea resources it claims exclusively, despite competing claims by Vietnam and other Asian littoral states. Each has experienced a mix of success and failure, leadership and backlash against its ambitions.

Equally significant, the internal stability of many second-world countries is not assured. Often it is unclear whether their populations will end up more resembling the first world or the third, or whether they will remain unequally divided between the two developmental poles in perpetuity. How can the two countries with the largest number of absolutely poor people in the world simultaneously be rivals to America on the world state?

But the argument is not that China or India can or will oust the U.S. as a global leader. To understand the post-American world, we must dispense with clichés about the East dominating the West, China replacing America, or the Pacific displacing the Atlantic. Indeed, the U.S.-EU dyad remains the world's largest free trade area and perhaps the world's only true alliance.

The emerging world order will be defined instead by complexity, even chaos, rather than hegemony and dominance. Many great powers will co-exist, some global and some regional, each of them viewing themselves as the center of the world, while forming multiple alliances of convenience and showing ever less deference to the U.S. This radical positionalism, and not a durable American unipolarity, will be the lasting outcome of the collapse of the Soviet Union. Like Organski before us, we should have seen it coming.