Could Mayors Rule The World?

LSE IDEAS |

By Parag Khanna

Leading U.S. political scientist Benjamin Barber visited LSE on Wednesday for a seminar to discuss the framing ideas for his current book project titled If Mayors Ruled the World.

Many know Barber for his provocative book from the early 1990s titled “Jihad versus McWorld,” but his influence extends very much into the fields of democracy theory (“Strong Democracy”) and intellectual history. Since 2001, Barber has been leading a civil society movement called Interdependence Day, an international event hosted in a growing number of cities around the world on September 12 of each year.

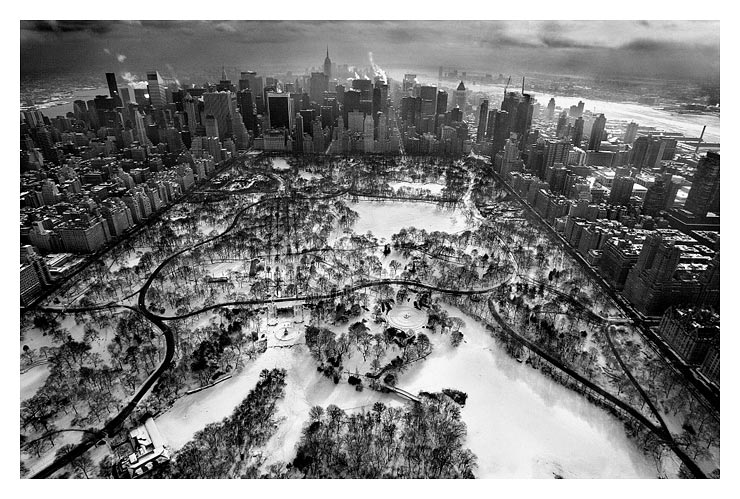

“If Mayors Ruled the World” is premised on the notion that of the three elemental political units — empires, nations, and cities — it is cities which have existed the longest and cities which today represent the level at which “things get done.” In an age where the tenets of the nation-state system — sovereignty, independence, and nationhood — are out of synch with the nature of global problems, cities represent the more appropriate scale for finding solutions, sharing best practices, and shaping emergent norms. As Barber puts it, “Radical interdependence requires that we respond to problems through the actors that are not jurisdictionally limited by sovereignty.” Barber believes that cities tend to act more non-ideologically and pragmatically than nation-states. Cities invite the other into themselves and form a collective with them, while nations are defined by exclusion of the other.

A number of current diplomatic processes illustrate Barber’s main argument. Whereas the intergovernmental climate negotiations have yielded little result, mayors have taken aggressive steps to counter greenhouse gas emissions and their joint proposals shaped the final Copenhagen climate summit text. The same is true for the Durban sustainability summit. The C-40 climate initiative (bolstered by the Clinton Global Initiative) is as significant as any other effort to combat climate change today. If anything, the success of inter-city cooperation may provoke national governments to become jealous and protective of their eminent domain in diplomacy. Barber pointed out that the US Supreme Court has blocked Washington, D.C. from banning handguns, something New York’s mayor Michael Bloomberg would like to do as well.

Rather than paint a necessary dichotomy between city action and states which must necessarily be “by-passed,” Barber argues that the city presents the right platform for aggregation and partnership among stakeholders such as international organizations, federal governments, municipal authorities, and civil society. Even if cities do become the locus of global problem-solving, thorny questions remain as to whether inter-city relations can be ideology-free, and whether or not such relationships are democratic and representative in nature given that only half the world’s population lives in cities (though this figure is rising rapidly).

Barber does not promise answers to these questions (yet), but his approach is very consistent with the broader theoretical and empirical literature pointing to a diffusion of power and authority in the context of a systems change towards a multi-actor environment.