Getting Leapfrogging Right: Adapting Tech Trends to Developing Nations

The Next Web |

By Sara Agarwal and Parag Khanna

Since the rise of mobile communications and the Internet, movements have emerged to leverage such technologies to for economic growth, social equity, improved education and healthcare, and other public goods. Under the rubric of “Information Communication Technologies for Development” (ICT4D), donor agencies, NGOs, companies, industry coalitions and other players have clamored to launch initiatives to help countries to bridge the “digital divide” or “leapfrog” to the latest—or next—technology standards.

But both the rapid pace of technological change and the cost of adopting new products have proven to be stumbling blocks. Emerging market government spending on ICT is expected to be $138 billion in 2014, yet many such investments—as well as many ICT related projects undertaken by the World Bank and other donors—fail to result in tangible and cost-effective social benefits.

Now a new generation of digital breakthroughs – cloud computing, big data, social computing, and 3D printing – hold the potential to deliver important social benefits, but only if we change how technology adoption is practiced. We argue that ‘leapfrogging’ should not be thought of as a one-off purchase but a process of incremental, low-cost acquisition of services.

The goal is not to leapfrog over Western economies, but to leapfrog over costly and redundant technologies and make better use of existing tools and services. By focusing on adaptable technologies that can be upgraded over time, countries can reach a higher technology standard that allows them to improve service delivery in the most affordable manner.

In this article we highlight these four key technologies and their potential benefits for developing countries across a range of areas from healthcare to education to transportation, and make recommendations for how various actors such as governments, donor agencies, and NGOs can collaborate on reforming procurement, mainstreaming, skill-building, finance, and other areas to make leapfrogging a sustainable reality.

Next Gen Tech: Cloud, Social, Big Data, 3D

Cloud Computing

The advent of cloud computing offers a potential breakthrough in achieving high quality IT services at far lower cost. Cloud products offer low-income countries the standardization and digitization of basic services such as verification, storage, document and workflow management, access to content), while outsourcing complicated processes and focus spending on leasing or licensing technologies rather than expensive hardware and backend systems that cost more upfront and require skilled technicians to maintain.

In other words, they can switch from the sunk costs of capital expenditure (CapEx) to the adaptable costs of operational expenditure (OpEx). Whether large or small, governments then pay only for only the services they consume and subscribe to, and can add optional plug-ins (for additional security and privacy, for example) to tailor or enhance their outcomes.

The World Bank has praised cloud computing as enabling a “shared infrastructure” that “pools resources, exploits economies of scale, achieves operational efficiencies, and saves costs.”

Already there are numerous examples of cloud computing streamlining government operations. In Albania, 14 separate ministries operated their own IT infrastructure, with more than 300 servers spread across dozens of locations and running a multitude of operating systems. This resulted in huge maintenance costs and variable service.

Now, the entire Albanian government’s IT infrastructure is hosted on a private cloud. Server provisioning time has been reduced by 70 percent, administrative costs have been reduced, application procurement time has shrunk to seven months, and ministries can focus more on citizen solutions.

Similar stories can be told from Panama to Tanzania. In the Indian state of Karanataka, Hewlett Packard’s eProcurement System now handles the full process of indenting, estimation, tendering, auctioning, and cataloging contracts in a single online portal that reduces the potential for corruption and has cut the selection period from four months to one and a half months.

The shared services cloud computing brings not only reduces government overhead but can empower entire populations. In the educational sector, for example, better online educational content provided through the cloud has the potential to address the classic challenges of developing country classrooms such as large classroom sizes, lack of local experts and lab environments in hard-to-teach STEM topics, and teacher training.

Where one-size-fits-all classrooms have for generations left weaker students behind, cloud-based devices that blend text with multi-media sources and adjust difficulty to different levels can personalize learning modules and spark critical thinking and creativity.

Cloud services also empower increasingly mobile and urban populations. In Turkey, where each municipality is responsible for its own public transportation, transport software company Kentkart has deployed a cloud-based real-time General Transit Feed Specification (GTFS) system that allows all passengers with smartphones to view the live location and arrival times of busses and metros.

Social Computing

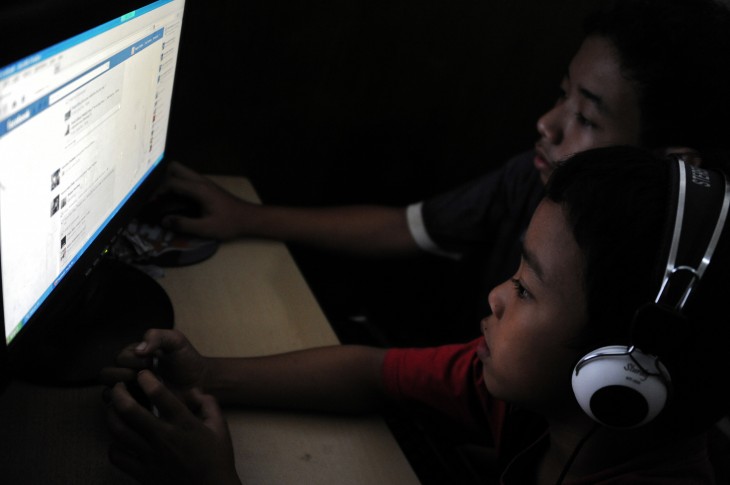

Wherever humans interact digitally, there is the possibility to find useful insights. The streams of unstructured data (stemming from real-time communications and postings from Facebook to YouTube) comprise a vast set of data that can be analyzed through social computing.

Social computing can be used to crowdsource suggested responses to difficult situations and decisions. They can also be used to anticipate crises. Twitter messages can provide an early warning on problems such as shortages of critical food staples, and Google Flu Trends analyzes search terms to estimate and geo-locate flu outbreaks.

These applications can help governments pre-position everything from food stocks to flu vaccines, as well as relief supplies during natural disasters.

Data sharing through to social connections can also enable employees working in government to take advantage of the collective knowledge within their organization to more effectively make and implement policies.

Big Data

Big data goes beyond social computing to leverage not just large datasets, but to interrelate them to find correlations that can help countries optimize policy and social welfare. Even more so than cloud computing, big data involves the modification of decision-making processes to include technology.

The examples of using big data to meet the crucial needs of emerging markets are also wide-ranging and promising. The agricultural sector has already benefited tremendously from data correlations, with farmers around the world now able to quantify harvests, correlate them to weather patterns and market demand, and maximize revenues.

Transportation is another critical area. In Abijan, the capital of the Ivory Coast, Orange Telecom launched a “Data for Development” program that used 15 million anonymized mobile phone call data-points to correlate commuting patterns to public transportation schedules. The result was the redrawing of the city’s major bus routes, reducing congestion and cutting commuting time.

Healthcare can also benefit from big data. In India, GE’s new artificial intelligence software called Corvix uses historical geo-location data to predict how diseases may spread through towns and where to best locate future hospitals.

3D Printing

One of the most exciting new areas of technological innovation with profound implications for developing countries is 3D printing (formally known as additive manufacturing), which allows geometrically complex objects to be fabricated using 3D model data and material printing devices.

3D printed matter could be used to make everything from product prototypes to replacement parts for industrial appliances; printing food is also a promising application under development. The potential for countries to leapfrog over costly industrial infrastructure is nearly limitless. Small-scale manufacturers and entrepreneurs can now produce items that would previously have required a much larger upfront investment, and potentially climb the competitive value chain far more quickly.

Some very promising experiments in 3D printing are underway that promise large-scale social and economic empowerment. TED fellow Marcin Jakubowski recently launched the “Global Village Starter Kit” that collects blueprint and designs for agricultural tools that can be 3D printed and used by farmers wherever the kit is deployed, reducing the cost and time required to replace worn or broken tools.

In India, 3D printing applications such as Fittle are being used to provide accessible Braille materials for the visually impaired. 3D printers are already used to make hearing aids, and distributing such printers to rural or peri-urban areas could allow for large-scale treatment of hearing loss at affordable prices.

One of the important environmental benefits of 3D printing is that it can make use of biodegradable plastic, which is often not possible in traditional manufacturing.

Where to go from here?

The key challenge developing country governments face is to enable better public sector service delivery amidst weak economies, poor infrastructure, resource stress and rising expectations from citizens. However, as the previous examples demonstrate, breakthroughs in low-cost, high impact technologies can indeed bridge market failures in infrastructure provision, enable the more effective and equitable provision of education and healthcare, and create new business models to reach the poorest citizens.

What then can be done to accelerate the adoption of these technologies across emerging societies?

The first area relates to procurement reform: how do governments buy and acquire ICT systems? The Office of the US Trade Representative estimates that up to 20 percent of a country’s GDP is made up of government procurement.

Enabling more innovation in the public sector procurement process today could allow for newer technologies in cloud computing and virtualization to save substantially on costs while allowing the governments that pay for them to get better performance solutions. Yet most public sector procurement systems across the globe do not encourage this kind of innovation, and de facto procurement standards promoted by organizations such as the World Bank in emerging markets do not currently offer an innovative alternative.

For example, the World Bank recently tendered a request for companies to bid on the provision of 3500 computers for the Ukrainian government. In conversation with the private sector, the government became convinced that a Virtual Desktop Infrastructure (VDI) would be a better and more cost-effective option, and substitute for in-house data service centers.

The World Bank’s procurement rules, however, did not allow for this switch to this system as it was not part of the normal procurement request or process. A two-part procurement process—inviting feedback on the tender to determine the best solution prior to the second phase of actual procurement—would bring innovation into the procurement process far more robustly.

Mainstreaming low-cost ICT is also a major challenge to spread the benefits of these new breakthroughs. Even though three-quarters of World Bank projects involve technology components, donor agencies have tended to stovepipe their technology programs to focus on narrow projects, missing opportunities to cross-fertilize them into other areas.

To counter this trend, the World Bank has launched an “Open Development Technology Alliance” to leverage the broad base of ICT knowledge residing in companies, governments, academia and civil society and share insights with their national clients. But such practices must reside within developing country governments themselves as well.

With donor support, governments can set up “innovation officers” whose main duty is spread innovative solutions across public services areas. This should be explicitly included in the “Economic Growth and Development Act” pending in the US Congress which calls for enhanced public-private partnerships in all development projects.

A third approach to spreading access to these low-cost technologies is skill building. Fully leveraging these innovations require management and operations by people trained in IT systems, analytics, and engineering.

The trend towards investment in vocational education that better links learning institutions to the labor market and emerging economic opportunities is especially relevant in developing countries. The private sector can play a critical role in spurring the creation of more market relevant educational modes.

Lastly, the challenge of financing innovative technology adoption must be addressed through blended funding models that deliver both economic and social returns. For example, Microsoft’s 4Afrika Initiative involves the roll-out of lower-cost power generation and Internet access across the continent.

Another novel approach is development impact bonds in which private entities (whether companies or foundations) invest in complex technologies aimed at broad social benefit, and collect financial returns from governments and donors when the results are demonstrated.

On the whole, financing must increase and blend, while business models for selling to governments should shrink to the pay-per-use level that characterizes the hugely successful “bottom of the pyramid” approach to supplying goods to low-income markets.

This model applies even to the more expensive featured technologies such as cloud computing.Development organizations and aid agencies could easily promote the use of this type of innovation among the governments they support as a cost-effective solution to procure more quickly and transparently.

Conclusion

For developing countries to leapfrog in the manner discussed here, the minimum requirement is basic level of digitization without which there is no data to store in the cloud, correlations to find, or social computing to monitor.

At the other end of the spectrum, proof of the possible comes from countries such as the UAE that has rapidly graduated towards converged infrastructure in which servers, networking, and IT management systems are all harmonized into a single framework.

The hardware and software breakthroughs discussed here make it possible for developing countries to switch to a more modular and cost-effective strategy for leveraging technology for development. But implementing this spectrum of technologies in developing countries will also require the collaboration of multiple actors, public and private, domestic and foreign.

If all stakeholders in the ICT4D arena focus on cost-effective and upgradeable technology systems with long-term financial models, then developing countries will indeed catch-up and keep pace with global technology standards.

Sara Agarwal is Director for International Finance Organizations at Hewlett Packard. Dr. Parag Khanna is a Senior Research Fellow at the New America Foundation, a non-partisan public policy think-tank based in Washington, D.C.