Bin Laden Assassinated, Not Martyred

CNN.com |

By Parag Khanna

In the decade since 9/11, many senior al Qaeda leaders and operatives have been killed in Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Yemen, Somalia and elsewhere, yet still all of these countries remain fragile at best and collapsed at worst.

For Osama bin Laden’s assassination to become a turning point rather than a Pyrrhic victory, the narrative of the event must be dramatically shifted away from rhetorical overtones about a “war of ideas” or “struggle for soul of Islam” towards a more neutral and universal appeal to a global rule of law.

President Obama set the right tone with his statement on Sunday evening that the “United States is not — and never will be — at war with Islam. … Bin Laden was not a Muslim leader. He was a mass murderer of Muslims.” For his criminal atrocities, bin Laden was assassinated, not martyred.

That it was American counterterrorism operatives who conducted the assassination on the sovereign soil of a foreign country is an even more important marker. Many see the assassination of rogue individuals as a violation of sovereign immunity and even “playing God,” a right that no nation can arrogate to itself. This is false. It is a powerful symbol of our collective evolution that individual perpetrators are targeted for their crimes rather than entire societies punished in wars.

Over the past decade, international law has evolved in such a way as to justify such direct interventions, if only we could act more quickly on the thicket of protocols and deliberations we have invented. The International Criminal Court which oversaw the trial of Serbian war criminal Slobodan Milosevic, has indicted sitting heads of state such as Omar Bashir of Sudan. The Responsibility to Protect (R2P) doctrine, ratified in 2005 by the United Nations General Assembly in 2005, sets forth a process for determining whether the international community can be obligated to intervene to prevent crimes against humanity.

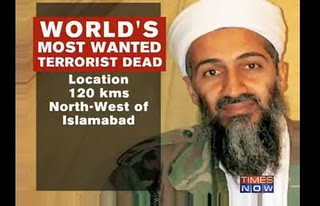

Where bin Laden was killed The core principle behind these institutions and treaties is that sovereignty is a responsibility, not a privilege. This applies not only to dictators and terrorist fugitives, but to the governments that give them safe harbor.

It is no secret that Osama bin Laden was hiding in plain sight in various locales in Pakistan for the past decade. While some have argued that this operation should be spun as having been conducted by Pakistani forces or disgruntled al Qaeda members would have let the Pakistani army off the hook from answering the difficult questions it must now face. Instead, this operation has sent a clear reminder to the many porous and poorly governed states that serve as safe havens for terrorist and criminal fugitives that others will extend the law into their territories if they fail to do so themselves.

We are currently living another test of this proposition in Libya. If Moammar Gadhafi had been assassinated in a drone strike or raid within two days of Benghazi falling to rebel forces, his own tribes would surely have been demoralized and been forced into a compromise. Instead, Libya is the site of small massacres — the term “stalemate” a euphemism for daily barbarism at Gadhafi’s hands. It takes only utilitarian common sense to determine the wisest course of action.

The arguments against political assassinations hinge on an overly legalistic commitment to sovereignty and a misplaced fear of retribution. It is precisely the accretion of a body of international humanitarian law that justifies interventions from Kosovo to East Timor and assassinations of figures like Osama bin Laden.

In order for new norms to push forward, old ones must die. Furthermore, the presumption that Western leaders will now be targeted in revenge neglects the multiple major terrorist attacks that have befallen Western nations since 9/11, and certainly also threats to heads of state. Terrorists have not needed bin Laden’s death to justify such attacks, even if they attempt to construe it as such in the future.

It is a sense of exceptionalism that convinces radical groups that their actions are morally justified. What is at stake then with the assassination of bin Laden is that there cannot be exceptions to the rule of law. The more this approach is articulated to grasp the moral high ground in the years ahead, the less the wicked will be missed when they are gone.

Parag Khanna, a former adviser to U.S. Special Operations Forces in Afghanistan, is a senior fellow at the New America Foundation and author of How to Run the World (Random House, 2011).