“Open democratic societies don’t block Google”

Fortune |

Interview by Anne VanderMey

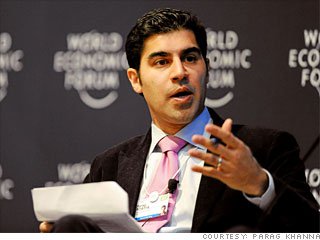

Foreign policy wunderkind Parag Khanna says revolutions in the Middle East could mean good things for the world – and for business.

There's a lot of reasons to be skittish about conflict in Libya -– high oil prices, another potentially deficit-expanding conflict, and more unrest in a strategically critical region. Indeed, sweeping speeches about freedom and democracy from the floor of the UN have done little to quell market fears.

But there's a bright side for business in what can seem like dark times, says Parag Khanna, a senior research fellow at the New America Foundation. Khanna is the author of the new book "How to Run the World" (Random House). It's a bold undertaking for a 33-year-old, but Khanna isn't a modest guy. A two-time author billed as a modern-day scholar-adventurer, the Indian-born, New York-raised London School of Economics PhD has travelled extensively in the Middle East, and lays out a roadmap for what he says is a new, and superior way of handling the business and politics of the region.

Here, Khanna talks with Fortune about the increasingly important role for US companies on the geopolitical stage, why today's youth-driven revolutionary movement will see more success than Middle Eastern revolutions of the past, and why (per Baron Rothschild's advice) "when there's blood in the streets," it really might be the time to buy.

Fortune: Recent weeks have seen revolutions throughout the Middle East and North Africa, often paired with brutal crackdowns. Now there's an multinational intervention underway in Libya. How are you feeling about where this is headed?

Khanna: I'm still optimistic. With so many of these regimes, we have to remember that whatever comes next can't be worse. There are scenarios where I don't advocate immediately trying to topple a bad government because you really don't know what's going to come next. But quite frankly, in many of these places, nothing could be worse.

Right now I'm optimistic about youth moving from disaffection to activism and using technology and pushing for accountability. I'm also optimistic that outside pressure to reform is going to intensify, particularly because of issues like energy security and so forth. There's going to be an upgraded effort to respond to that, because governments will be forced to answer to foreign interests and investment. These economies are really suffering in light of what has happened. Just look at Egypt, where 60% of the economy was dependant on tourism, which got hurt very badly. They're not just going to be able to rearrange deck chairs and impress anyone at this point, as you can imagine.

So there's a light at the end of the economic tunnel?

In some cases, you can actually expect these markets to now grow as a result of the upheaval. These governments have to create jobs, they have to invest in infrastructure, they have to provide for the people. They're going to become larger consumer economies as they open up. Longer term, all this might be good for the economies in the region.

It's very important to point out that things are going to move very slowly. But still, let's be optimistic and not cynical. Some experts are fear-mongering with claims like, "The Muslim Brotherhood is going to takeover. Is this what you want? This is going to be a nightmare." And that, quite simply, betrays a lack of understanding of Egyptian politics. The majority of the people that want their basic, secular needs met before they want Muslim Brotherhood rule.

What are the potential economic impacts of an international conflict in Libya?

Without actually stopping the aggressive forces by military or diplomatic means, orders will continue to come from Tripoli. So military action will likely continue in various ways until Gaddafi is actually dead. I think the economic impact will be limited unless all of Libya's oil is actually take offline. There are still a number of open scenarios, including splitting the country. Libya is not a natural state by any means. It's an example of what I call "post-colonial entropy" in this book, meaning it's been in a slow process of decay and fragmentation ever since independence.

How is the role of corporations going to change in the Middle East going forward?

That's actually a really good question. If the traditional regimes stay in power, they may be perceived as agents of Western interests and be subject to greater scrutiny, even blockage. If traditional regimes are not still in power, then I think they don't have anything to worry about. Open democratic societies don't block Google (GOOG). This is one of the reasons why I'm optimistic. Because governments are going to improve in these countries, you're going to see some economic growth and more participation. This is obviously good for Western exporters and so forth. So I think we're ultimately going to see more integration with global markets in the Arab world.

Especially during the revolution, we heard a lot of fretting about Western business interests in Egypt. Is there the potential for a positive economic outcome?

Well, Tunisia is a good example of that. Tunisia had been praised for many years for being the most competitive Arab economy, for having good infrastructure, high levels of education, substantial foreign investment, all of these kinds of things. It just happened to also be extremely corrupt. Because of that foundation, Tunisia could wind up taking off after this. There's a high price to pay in countries where all the business deals have to go through someone connected to the ruling family.

Egypt is another interesting case. It's been a country that's been extremely difficult to reform. I think now you're going to see the arbitrary powers of the president curbed, along with a much more technocratic cabinet that has to answer to the people on social welfare. It will also have to answer to international creditors and the international financial community. It's going to have to be much cleaner than previous governments. Really, you couldn't do less than Mubarak was doing, so it can only go uphill.

Considering all the handwringing we're seeing on TV and in columns, that's a fairly counter-intuitive position.

I don't think it can be better said than the old cliché, "Buy when there's blood in the streets." Goldman Sachs (GS) put Egypt in their "Next 11" category, mostly because of the fact that it had a large population. Because of its government, though, it certainly didn't belong there. Now, potentially, in a post-Mubarak regime, in the next 10 years Egypt could year become a genuinely worthwhile investment-grade emerging market.