Against Growth Market Pessimism

HuffPost |

By Parag Khanna

SINGAPORE — In 2009, the Financial Times and other media confidently predicted that China’s economy had “hit a wall” and that China’s entire political order could come crashing down as both imports and exports collapsed in the wake of the financial crisis. By 2010, Western media had changed its tune. After China undertook a massive fiscal (rather than monetary) stimulus focused on infrastructure and job creation, headlines suddenly read that developing economies were geared to lead the global economic recovery. The contrast within just one year reflects our broader ambivalence and ignorance about the dynamics of high-growth markets, none of which (save for perhaps Poland and Israel) are located in West.

A new variant of this growth markets pessimism has emerged in recent months, with even the man who coined the term “BRICS,” Jim O’Neill of Goldman Sachs, piling on. In August 2013, he told the Wall Street Journal, “If I were to change it, I would just leave the ‘C’,” for China. It’s a stunning admission since his original idea was not merely to make an acronym out of large and populous countries, but to identify those with sufficient diversification and complementarity to grow counter-cyclically as well.

There is no doubt we live in a G-3 geo-economic landscape, with the U.S., Eurozone and China dominating global calculations. But economic convergence continues across all regions, something the growth market pessimists–whether in 2009 or 2014–ought to remember. The ten-member ASEAN grouping is the world’s fastest growing region, Africa remains largely on the fast track, and Latin America’s 800 million people represent almost two-thirds the GDP of China.

To claim that the fundamental driver of emerging market growth has been the U.S. Fed’s quantitative easing policy and not investment, consumption, and trade, is a narrow and warped reading of current events. While Ben Bernake’s hints at Fed tapering last summer roiled emerging market equities and currencies, it has certainly not meant their unraveling. Western commentary on Asia would have led one to believe that the 1997-8 financial crisis was circling back to torment the region. But this time around, Southeast Asia has far larger reserves, more flexible exchange rates, healthy bank and corporate balance sheets, and even higher investment rates. With Sino-Japanese tensions high, Japan has decreased its FDI in China by 31 percent while raising its FDI into ASEAN by 55 percent; overall it now invests close to $10 billion in ASEAN, double what it does in China. Why declare that China is the only true representative of growth markets when major investors are diversifying away from China?

What most economists miss when analyzing individual emerging markets are the intra-regional and inter-regional foundations of their growing resilience to shocks emerging from major Western economies. ASEAN’s exports to the sluggish Eurozone, for example, have been hit substantially since the financial crisis, but its internal trade volume has risen to 30 percent of its total trade in the same period. In 2015, it will launch a free trade area comprising over 600 million people and a GDP substantially larger than India’s.

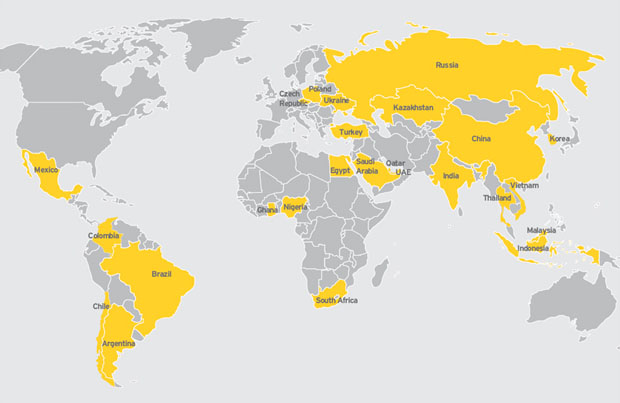

The inter-regional dimensions of the global economy are equally powerful in explaining more robust distributed growth. Over the past decade, trade and investment flows between South America, Africa, the Middle East, and East Asia have risen anywhere from 700 to 1500 percent–yes, quadruple digit growth. Of course, what was once called “South-South” trade has risen from a very low base, but today China has surpassed Europe and America as Africa’s largest trade partner. As new investment and trade flows, and supply chain connections, flourish across various growth market regional pairs, a new pattern of diversified interdependence has taken shape. De-coupling is neither a reality nor a benchmark nor a goal–yet it is increasingly clear that globalization does not in fact require a Western anchor.

Not all growth markets are promised a linear path to success, and instability surely lies ahead for the ill prepared. Those with excessive credit growth, high short-term external debt, and weaker reserve positions remain at substantial risk of volatility stemming from rapid capital outflows. According to a new Economist index, the most vulnerable countries are in Latin America and Eastern Europe. Turkey tops the list, with a plummeting lira and misallocation of capital causing the credit bubble to pop and sparking widespread unrest across the country. Other developing country heroes such as Brazil and India have also witnessed huge economic setbacks in the past couple of years owing to very low infrastructure investment, which weakens economic and social mobility and reminds us of the narrow base of growth that plagues many emerging economies, including the Middle East.

Still, we should not underestimate how the forces of demographic growth, urbanization, middle class formation, economic openness, institutional modernization, and infrastructure renewal have been and can become ever more the foundations of robust worldwide growth. Smart Western exporters such as Germany are well ahead in capitalizing on these trends: Germany’s intra-Eurozone trade is falling while its exports to emerging markets are expected to reach 70 percent of total trade by 2025. The U.S. is keen to ride the global growth wave as well. Currently it is negotiating both the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) with Europe and the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) with Asia. The former would harmonize the U.S.-EU regulatory landscape and reduce the remaining inefficiencies among the Western economies, and the latter could help break-up inefficient state-backed monopolies and unfair competition in Asia. The more seamless global trade and financial integration becomes, the more we can continue on the path away from gravity models and regional blocks towards truly global complementarities.

Growth markets have also become key power brokers in the arena of international economic diplomacy. Many have noted their growing influence at the World Bank, whose outgoing Chinese chief economist has strongly advocated a plurality of growth models, and the IMF, which recently issued a report endorsing the limited capital controls that have helped protect growth markets from excessive financial volatility. At the most recent G-20 summit in Russia, there was also notable evidence of emerging market influence on the agenda. Beyond the perfunctory statements about the need for coordinated stimulus and limited protectionism, the G-20 produced a formal statement and subsequent report on the need for investment in job-creating infrastructure to be the backbone of a broad-based global economic recovery, advocating jump-start investment funds, more multilateral risk insurance, and long-term private capital flows into infrastructure projects.

The G-20 economies have not only endorsed this approach, they should act on it. Growth markets are clearly pursuing a smarter path towards their own economic development, and are wisely recruiting Western investors and institutions–and each other–into the process. Globalization is alive and well.

Read more article: Geotechnology and Global Change