Permeable Lines on the Grand Trunk Road

The New York Times |

By Parag Khanna

Next to the Mideast, South Asia is the world’s least friendly geopolitical neighborhood. Indeed, the toll in the Kashmir conflict – 50,000 deaths since 1990 – is about triple the number of fatalities in the Israel-Palestine conflict since 1948. To this day, the neighbors don’t get along: no two states among Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Nepal and Sri Lanka enjoy truly constructive and unsuspicious relations. After the Mumbai terror attacks of 2008, carried out by a terrorist group based in Pakistan, there seemed little hope for any reconciliation between those two crucial nations.

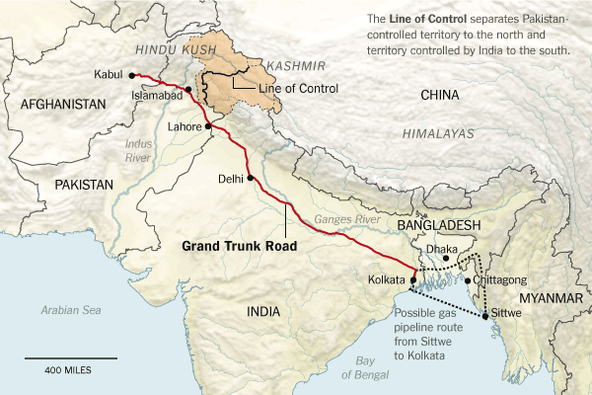

And yet in recent months, particularly with the invitation to New Delhi of all neighboring heads of state by recently elected Indian prime minister Narendra Modi, an ambitious agenda has emerged around visa liberalization, infrastructure development, trade corridors, energy cooperation and disaster relief. Making good on this vision would require nothing less than a proper remapping of this frail post-colonial zone along the ancient Grand Trunk Road that links Kabul to Chittagong over a forbidding 1,500 miles.

One highly strategic portion of this highway is in Afghanistan – the stretch where more suicide bombings recently killed Afghan and NATO troops. A dozen states in the region, in addition to the U.S. State Department, endorse the “Silk Road Through Afghanistan” strategy, a plan to increase infrastructure connectivity, boost job creation and build people-to-people ties across the region's borders. But while China and Iran would clearly benefit from safe east-west corridors for Iranian energy and Afghan lithium and copper, it is a revitalized north-south Grand Trunk Road that would bring genuine stability to South-Central Asia.

As the U.S. withdraws almost all remaining forces from Afghanistan, the region can either return to the 1990s (with Pakistan’s policy of “strategic depth” undermining what little central authority exists in Afghanistan) or it can pursue commercial corridors to access Central Asia’s energy resources and markets. Given their dire energy shortages, Afghanistan, Pakistan and India all need to cooperate fully in the development of the Iran-Pakistan-India and Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India natural gas pipelines. Instead of fighting over arbitrary colonial borders, it is these roads and energy conduits that should be considered the sacred lines on the map.

Certainly one new political line could be drawn — or rather converted from dashed to solid. This would be the Line of Control in Kashmir. Rather than piecemeal delegations crossing this contested border, it could become a full-fledged international crossing for meaningful trade, while the Indian and Pakistani militaries could still protect against terrorist intrusions. That is already happening at the main Wagah-Attari border, which the two neighbors' commerce ministers recently agreed would remain open 24/7 to trade.

Now would also be an ideal time to extend the Grand Trunk Road even further into Myanmar. The headlines from the region highlight the alarming religious violence between Bengali Muslims and Buddhists in Myanmar – but all the region’s leaders seem to see the potential of a gas pipeline from Sittwe on the Bay of Bengal through India’s northeastern states of Mizoram and Tripura and crossing central Bangladesh to Kolkata. India, which has been losing out to China for influence in Myanmar, could finally take advantage of Yangon’s new desire to diversify partners (and exports) away from China alone.

Three major cities along the Grand Trunk Road – Lahore, Delhi and Dhaka – now lie in three separate countries, but they all owe their existence to the fertile Indo-Gangetic Plain. Redeveloping this road and uniting the region's agricultural productivity would finally make South Asia much greater than the sum of its underdeveloped parts.

Hemmed in by the Indian Ocean, the Himalayas and the Hindu Kush mountains, no South Asian state can extend its influence very far beyond the region. They are bound together — and might as well start acting that way.

Read more:

New BRICS Bank a Building Block of Alternative World Order Should Every Country be Like Singapore? Reimagining Cities: Transforming the 21st Century Metropolis