Review of “Who Owns the Future?” By Jaron Lanier

San Francisco Chronicle |

By Parag Khanna

America's technology sector is producing ever more accomplished thinker-doers. It's not enough to just code new software or launch companies; the best and brightest tech titans have also become publishing stars, notably Bill Gates, Eric Schmidt and, of course, Ray Kurzweil. Into this stream comes Jaron Lanier, a pioneer of virtual reality whose intellectually eccentric and nomadic background reminds one of Kevin Kelly and Stewart Brand. Lanier's first book, "You Are Not a Gadget," was a rough and fragmented manifesto, profound in parts, rambling in others, but cautiously non-prescriptive.

"Who Owns the Future" shows the Berkeley computer scientist as a much more wide-ranging thinker and advocate, embedding technology in the context of the rapid economic transformation and dislocation it is causing. He calls software "the final industrial revolution," mediating and subsuming all other industries and jobs, from driverless cars to 3-D printing to robotic nurses.

As robots replace Chinese workers as the bogeys of the American labor force, the technology-economics nexus is becoming a crowded field, with recent books including Chris Anderson's "Makers" and Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee's "Race Against the Machine." What differentiates Lanier is his deep understanding of the technologies at play and where they are headed (captured in amusing scenarios conjured throughout the book) and his laser-like focus on the monopolistic economies of data.

"Who Owns the Future?" is a title to be taken literally. Economics, according to Lanier, has become cosmology in the post-financial-crisis world. That's his polite way of saying "intellectual house of cards." What is left is something Lanier is well suited to dissect and reconstruct: an information system.

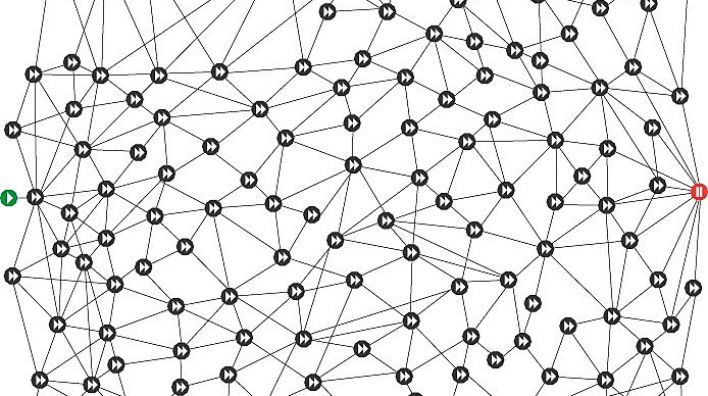

Lanier has had a front-row seat for the genesis of big data-nomics. Some of his erstwhile subversive chums from the hacker movement are ironically now the billionaires getting rich by hoarding the general public's data into "Siren Servers," his foil throughout the book. Their ability to treat humans like electrons has skewed the information economy more toward feudalism than capitalism.

Not unlike rare-earth-mineral miners in African countries, money is flowing to those who aggregate data, not those who provide the raw materials. Orbitz kills travel agencies, Amazon kills bookstores, Coursera and Wikipedia kill non-elite academics.

These are accidental monopolies, to be sure, but they displace people nonetheless. Where many see conspiracies, Lanier is fairer, pointing to complexity as the culprit. Automation technologies that have displaced manufacturing are a symptom of this deeper disruption, not the cause. Echoing Marc Andreessen, who famously wrote that software is "eating the world," Lanier declares that factories and banks will disappear this century. The data we consider "free" is an illusion, for in the long run it terminates us.

So what is an ordinary person to do to reclaim his "digital dignity"? The second half of Lanier's book delivers his prescription in a mix of mediation and manifesto. He points out that "digital information is just people in disguise," and reaching for an apt economic analogy, notes that if they refuse to or cannot play along with the data masters' pyramid (a la the subprime-mortgage fiasco), the system collapses.

The free will or agency of the individual has always been central to Lanier's worldview; he accuses other technologists of wanting the Starship Enterprise without Captain Kirk. This now merges with a discourse on rights and the social contract. Whereas most authors look at your personal relationship to data as a privacy issue, which is political and legal, Lanier infuses a commercial dimension. Rather than giving away our personal data mindlessly for free, it should be priced based on mutual agreement but also legacy value (a measurement of the long-term value to humankind).

Rather than celebrating everything becoming "free," the secret to ensuring the creation and sustenance of a digital middle class is for information to have a meaningful price. Lanier is to the monetization of data what the Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto is to property rights: the champion of the dispossessed, calling on them, and their governments, to recognize their value and bring about a more humane economic order, one shaped more like a bell curve than a winner-take-all distribution.

As he has done in the past, Lanier celebrates technology as a tool of creativity, pointing to the promise of profitable mashups versus the stifling role of intellectual property protections, which should be more rapidly phased out. There is some evidence for his new economic paradigm, whether Kickstarter, Etsy, Ebay or Craigslist. But he confesses that creating a "mass market for ordinary people" rests on the shaky assumption that the masses "have something to offer."

No doubt there will be new kinds of accountants for nonmonetary transactions in whatever comes after Second Life, as well as more digital interface designers, but the massive shortcomings of one key sector - education - to retool populations for an age of digital networking remain mysteriously unaddressed in this book. Instead, the solution to the hegemony of "Siren Servers" is more such servers, but ones operating on the model of individual commercial rights he advocates.

There is also a strong role for government in guaranteeing access to data and digital identity protection, and also a digital central bank to be a financial backbone. But isn't this the same Congress that just tried to pass the Stop Online Piracy Act? And would a digital Ben Bernanke simply intoxicate the masses with trillions of zero-interest credits?

Whatever its flaws in not presenting a detailed master economic plan for the dwindling middle class, "Who Owns the Future?" is a useful corrective to what Lanier describes as Silicon Valley's obsession with Moore's Law, which is revered "like all ten commandments rolled into one." If a digital exodus begins, Lanier will play the role of Moses.