The Neo-Renaissance Man

Asia Times |

How to Run the World: Charting a Course to the Next Renaissance by Parag Khanna Reviewed by Pepe Escobar

Steve Clemons of the New America Foundation describes Parag Khanna as a "global futurist". Now that's a sterling job. Even apart from the obviously sexy Isaac Asimov overtones, this entails crisscrossing the planet identifying future trends and getting paid for it. On the other hand, it's true that an array of single-minded wonks slumped in their think-tank chairs also love to deploy this job description.

That's certainly not the case with Khanna - a young, dynamic, hyper-connected insider who's actually been all over the world armed with a good education, and has a sense of history, no prejudice, an open mind and delightful conversational skills. It doesn't hurt, additionally, that he directs what the Washington-based New America Foundation calls its "Global Governance Initiative".

The core, very appealing, idea in this book is that "mega-diplomacy" - a dizzying, ultra-high-speed networking of institutional and informal political/economic/cultural actors - will rescue us from our current, chaotic neo-medieval valley of tears towards a possible next Renaissance. Khanna defines mega-diplomacy as a new "software" that "unleashes the resources of governments, corporations and NGOs".

Problem is, the new software may be a Linux; but it may also turn out to be bloody Windows all over again.

Khanna argues that even though globalization was like a big bang, producing an accumulation of fragments, all these influential new actors may be strategically recombined because of technology. Although many may recoil in horror at the concept, he's in fact calling for a "coalition of the willing" - in this case "ministries, companies, churches, foundations, universities, activists, and other willful, enterprising individuals" capable of, together, running the world.

OK, a choir of discontent can already be heard arguing that globalization was essentially a fabulous opportunity for the US and former European colonial powers to take over markets and economies of the rest of the world, until China stepped in and virtually monopolized the whole game.

Khanna counter-attacks with his best example of public-private collaboration - the Internet. Fair enough; but the discussion should get really serious only after one sees how the US government wants to deal with WikiLeaks, which, by the way, has just bombed the myth of traditional diplomacy to smithereens.

Apart from the usual government/institutional suspects, Khanna includes an array of extra players in the new rulers of the world, mostly powerful NGOs such as the Gates Foundation. These players are particularly fond of the global conference circuit - from the annual bash at in Davos of the World Economic Forum (WEF) to the seductively mysterious Bilderberg Group. Khanna delivers what's in fact a eulogy to the WEF (the "archetype of the new diplomacy"); but he could have also examined the activities of the parallel World Social Forums which - granted - were filled with redundant anti-imperialist rhetoric but always managed to raise modest and in many cases very sound proposals under the banner of "another world is possible".

Then there's the Boao Forum for Asia, on Hainan in China; the Aspen Institute's Ideas Festival; and what seems to be Khanna's favorite - the Clinton Global Initiative (60 heads of state plus hundreds of business leaders and NGO people from 90 countries). At the heart of all this activity there are scores of philanthropic foundations led by a sponsor with big ideas for reshaping the world.

Granted, that's much better than the 21st century plutocrats who actually rule the world "growing rich in their sleep" - to borrow from John Stuart Mill. But that does not make "stateless statesman" George Soros - who cares for nothing but his own global strategy - a selfless practitioner of "mega-diplomacy".

Much more appealing is Khanna's take on the new breed. But as much as Generation Y supports total communication, no trade barriers, migration, multiple identities (not to mention multitasking), equality and ecology, it's also not clear that it is practicing mega-diplomacy. Rather, its best and brightest seem to be on a mad dash to find the insight, the algorithm or the technology that can literally change the world on its own, way beyond mega-diplomacy.

Anyway, it's always refreshing to read an author reminding us: "A millennium ago - in the pre-Atlantic era - the world was genuinely Western and Eastern at the same time." Or that the world is actually not run by coherent states; instead what we have are "islands of governance". As for "mega-diplomacy", it may be a more seductive concept to describe the global scrambling for positioning as the American Empire declines; new tenants taking possession of what used to be part of the real estate of sprawling US foreign policy.

The US has squandered too much "political capital" (Dubya, anyone?) to prevail in a remixed global social contract. But it can reinvent some of its global leverage - if it reinvents itself. At least there are some visible signs already. Khanna points to American universities - from Georgetown to NYU - that are configuring themselves as the friendly face of US foreign policy in the Middle East, "educating the next generation of Arab entrepreneurs".

Then there are the real facts on the ground in the long march towards a new world order. The BRIC countries - Brazil, Russia, India, China - are already involved in deeper coordination inside the Group of 20 - especially in terms of development cooperation. They are definitely not betting on a war economy and military expansion as the axis of their foreign policy and economic development. Khanna does recognize the G-20's merits - "twenty hubs and no HQ". And he certainly sees the UN Security Council, as much of the world does, as a "club of abusers of privilege". Yet it's almost by accident, in one of the book’s chapter titles, that he touches the heart of the matter: "Who has the money makes the rules".

And that's the problem with mega-diplomacy. Whatever the influence of new actors, the eventual new rules of the game will be spelled out by the big powers, especially the US and now China, and the global plutocracy, especially financial - what Zygmunt Bauman would define as the superstars of liquid modernity.

There's no way to foresee what this brave new post-neo-medievalist world is coming to. (Just an example: did anybody foresee the sudden collapse of the Soviet Union?) One wishes to be as dynamically optimistic - let's say Kant with a touch of Hollywood - as Khanna. But try reading master architect/geographer/futurist Paul Virilio, for instance, in The Futurism of the Instant: Stop - Eject (Cambridge, Polity), and his dramatic take on "the end of history" as an optical illusion masking the end of geography, as well as the "trans-political tragedy of ecology". If we compound the current neo-medievalism with the current energy and water wars, plus pollution of land and seas, plus climate change, then the future is as bleak as the Mayan apocalypse.

Some may even get suspicious that Khanna uses a much sexier spin to arrive at the same conclusions deployed by Pentagon apologists: that this current global "anarchy" is unrealistic, and we need order, in their case imposed by the Pentagon, in Khanna's case arrived at by a concert of un-selfish, dialogue-bent actors.

Khanna does try hard - with great merit - to go beyond Kant. Kant proved that we can't grasp the inner nature of anything we perceive; the most we can aspire to is to know the mechanisms for understanding that are hard-wired into our brains. But Goethe still does seem to prevail against Kant; we are still in many ways living the dark side of the Enlightenment. To top it off, Asia is in a much more enviable position - beyond the Enlightenment altogether (Asia's enlightenment is more Buddha than Voltaire).

Beware of what you wish for. Khanna erects Jean Monnet, the father of European unity, as the "most inspirational figure for 21st century diplomacy". Monnet was a true humanist, no doubt, a visionary and a global statesman. But were he alive to see what the European Union has become - not to mention that gargantuan bureaucratic hellhole, the European Commission - he would have a heart attack.

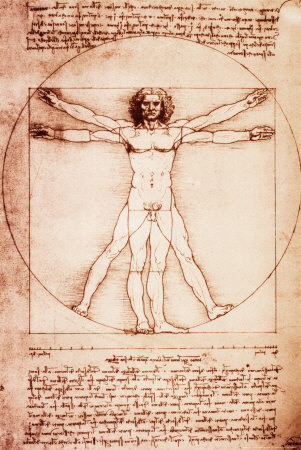

Moreover, in our transition from neo-medievalism to a possible new Renaissance, it's hard to see a counterpart of the Florentine Medici, counseled by a neo-Machiavelli, sponsoring a neo-Michelangelo or a neo-Leonardo da Vinci. Gates, Soros, Bloomberg - certainly none fits the part. Khanna himself defines the new Renaissance as "about universal liberation through exponentially expanding and voluntary interconnections". Try convincing Pentagon generals about that.

Immanuel Wallerstein or David Harvey would tell us that the real game-changer could be the coming of a new world system, beyond the financial turbo-charging of capitalism. Probably this won’t happen before 2040 - if that. It's fair to argue that only after a radical systemic transformation - towards a more equitable distribution of wealth privileging the global common good - is there a realistic possibility of envisioning the next Renaissance.

None of this mars Khanna's laudable effort. Breathlessly bristling with at least an idea per paragraph, it's refreshing to be reminded that "international bureaucrats should expect nothing less than a technologically empowered revolt". Makes one think of May '68 - "we want the world and we want it now". We still do. Gotta give 'em hell, even in undiplomatic ways.

How to Run the World: Charting a Course to the Next Renaissance by Parag Khanna. New York, Random House (January 11, 2011). ISBN 978-1-4000-6827-2. Price US$25, 272 pages.

Pepe Escobar is the author ofGlobalistan: How the Globalized World is Dissolving into Liquid War (Nimble Books, 2007) and Red Zone Blues: a snapshot of Baghdad during the surge. His new book, just out, is Obama does Globalistan (Nimble Books, 2009).