Time for a post-dynastic democracy

Mint India |

By Parag Khanna

Every Indian election brings high hopes of quantum leaps in India’s quality of governance, economic performance and global standing, usually followed by the disappointing realization that changing personalities doesn’t change systems. In the US it has become much the same. What Indian voters now seek is the lowest common denominator: change itself. Now, once again, they have change. But is it a change of personalities or systems?

India is a shining example of the late Harvard professor Samuel Huntington’s famous dictum that what matters more than the type of government is the degree of government. Inequality, devolution and poor infrastructure guarantee that little will change structurally in India for the next half-a-decade at least. It is geography—more than democracy—that holds such a diverse and diffuse civilization together.

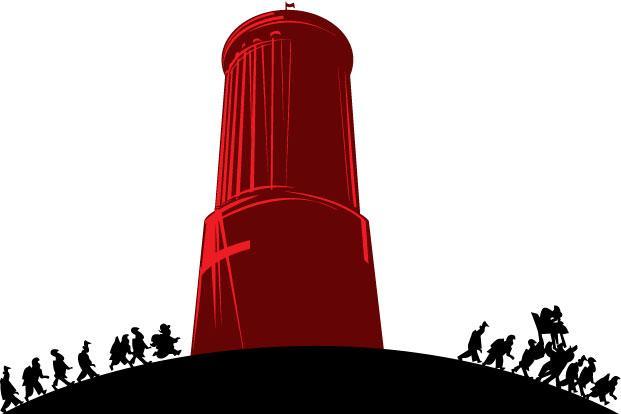

India now needs to move from process to performance. One deep change on the cards with the Congress’ loss of parliamentary majority is the end of India’s dynastic political culture. One can tell from any distance that it isRahul Gandhi himself who least wanted to become head of state. It is a sign of the lack of cultivated depth in the Congress leadership and the immature expectations of a sentimental public that someone so utterly unqualified and uninterested would be the party’s face. It tells us much of what we need to know about this election—and what needs to change. Rahul has been right about this: It is the system that needs to change, not just the individual leaders.

After a decade of empty slogans ranging from “India Shining” to “Ch-India” to “BRICS”, the fundamentals haven’t changed: India is much more like Africa than China when it comes to measures of per capita income, the number of absolute poor people, life expectancy, literacy, mobile phone penetration, foreign investment, corruption, and many other measures of the genuine state of affairs in countries.

We should not confuse appreciation of India’s democracy with envy for its political model. No country inside or outside Asia thinks India is a great power. Hosting parties at Davos and staging a Formula-One race don’t make countries great powers. Being the world’s largest democracy, a “civilizing power”, having lots of Bollywood and diaspora driven soft power, and other clichés rolled out by elites don’t cut it. Even a coveted seat on the UN Security Council would make no difference.

To become a great power, there is no substitute for solid infrastructure, productive industries, high employment, a competent civil service, universal education, law and order, and a long-term diplomatic vision. Great powers such as China have the capacity to simultaneously pursue their domestic priorities and international ambitions. India should be no different. What Indian voters have ratified needs to shift from political agenda to policy practice through long-term financial commitments, public-private partnerships, special economic zones, and other initiatives not subject to meddling and corruption. This accounts for the success of Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh—what other Indian states should replicate but with more national support.

Modi has rightly emphasized “24x7” power for all of India as a major deliverable—hopefully one that can be executed alongside completing the long-overdue Golden Quadrilateral highway network that his BJP predecessor Atal Bihari Vajpayee had championed. India’s 700 million rural population needs this connectivity (in addition to better irrigation and other agricultural technologies) to get goods to markets here and abroad. Physical infrastructure is no less important for empowering entrepreneurs. World Bank studies have shown that China’s so-called “white elephant” projects such as high-speed rail and massive new cities are nothing of the sort; in fact they have unlocked tremendous labour mobility and productivity. Only then will market deregulation, easing access to capital, and other soft measures have widespread impact.

Economic empowerment is the solution to India’s myriad internal fissures from Kashmir to Manipur to Chhattisgarh as well. India’s strategic geographies should be leveraged to build connective corridors for exporting minerals and boosting cross-border trade with neighbours. Instead, tensions remain inflamed in Kashmir and the government has no strategy for extracting iron ore and bauxite in a way that benefits marginalized tribal populations.

Yet witness how the five members of the East African Community—Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Rwanda and Burundi—have learned to bury the hatchet and forge cross-border rail, highway, road and power projects while coordinating investment flows from China. If India wants to be a global player, its task is first and foremost to shed post-colonial mentalities in its own neighbourhood.

India has little by way of a serious grand strategy, but evolving its regional relations to a new plateau of not just “friendliness” (Narendra Modi’s vague term) but significant synergy would be the best place to start. Indeed, only a stable and cooperative South Asia can change the game with respect to China’s manoeuvres from the Bay of Bengal to the Arabian Sea and give India a more confident maritime posture bestriding the world’s key shipping channels.

None of these priorities should depend on which party governs India now or in the future. Changing India’s system to lock in these strategic steps matters more than the outcome of this election—and the next one as well.

Parag Khanna is a senior fellow at the New America Foundation and adjunct professor in the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy at the National University of Singapore.

Read more article: A World Reimagined