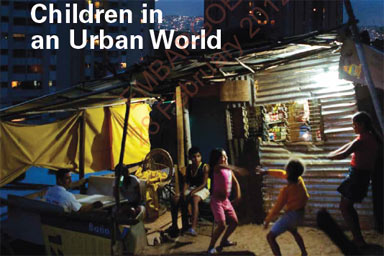

UNICEF Q&A on “The State of the World’s Children 2012 – Children in an Urban World”

UNICEF |

On the occasion of the launch of The State of the World’s Children 2012: Children in an Urban World, UNICEF’s communication specialist Tobias Dierks asked Parag Khanna, one of the world’s leading geo-strategists, what impact urbanization has on our lives, why he thinks that cities are the “locus of global problem-solving” and how children’s rights can best be protected in an urban world.

“If children’s rights will be achieved anywhere, it will certainly be in the cities.”

Q: By 2050, two thirds of the world’s people are expected to live in towns and cities. How will this change our cities? Is this a rather scary perspective or something we should be looking forward to?

A: We already live in a majority urban world, and we can feel the consequences – and appreciate the opportunities – well before we get to 2050. There are very few megacities in the world that don’t have enormous income stratification. Perhaps only Tokyo really qualifies. Across Latin America, Africa and Asia, the cities of over 15 or 20 million residents feature enormous income inequality. These cities are also in the countries that have large populations of youths and children, so that the problem of urban inequality is also a problem of lack of opportunity for young people.

Q: You call for a worldwide city performance index. What does this mean and how can such an index help the cities’ poorest? What child-specific data would you propose incorporating into the index?

A: We absolutely need a city performance index to measure the specific conditions and trends in the world’s major cities. National data around major issues like education levels, income, access to fresh water and other factors are heavily skewed because of the disparities between urban and rural areas. We need those data to identify gaps – even increasingly better geo-locate – and this can lead to better policies to remedy shortcomings in neglected areas. Comparing across cities in different countries and regions can hopefully engender a certain status competition to improve performance (something we have already seen when it comes to things like the Transparency International Corruption Perceptions Index). Some of the most important things we need better data on include children’s access to medical care, sanitation and education in major cities.

Q: In many publications and interviews you emphasize the important role of cities as motors of economic development worldwide. Will an “urban world” be a better, wealthier place to live? Are the residents of these cities better off in terms of education, health and opportunities?

A: In general, throughout history, people living in cities have had a higher standard of living than those outside them. Cities are certainly the locus of the world economy: The data that underpin most precisely the migration of economic power away from the West, for example, are based on a survey of 700 cities, not just national GDP. Remember, though, that because urban populations are growing so quickly, millions of people in megacities live in makeshift tenements in teeming slums, and authorities not only don’t provide health care or sanitation, but in some cases also actively inhibit such service provision and instead practice violent slum-clearing. So it is difficult to generalize about the quality of life within a city because people’s experiences are so disparate.

Q: Exploitation of children in cities and particularly in slums is widespread. At the same time you describe slums, such as Dharavi in Mumbai, as places “driving economic activities” that attract huge investments. Is it possible to have an urban centre that upholds the rights of all, while driving the country economy forward? In reality, isn’t this economic growth built on the shoulders of children?

A: Both such phenomenon - economic growth and exploitation of children - appear to be true at the same time. On the one hand, a place like Dharavi in Mumbai is a major centre for recycling cardboard, metal, plastics and other materials. Telecom operators and retail chains are pushing hard to capture the ambitious but low-cost markets represented by productive slums. On the other hand, there is no doubt that children are seen working in such places – the same is true in similar places on other continents. The enforcement of international labour norms is scarcely attempted in slums. There is hope, however, that the growing attention such slums receive from investors brings in the kind of capital that results in families having more disposable income with which to send their children to school.

Q: In addition to their economic potential you describe cities as the “locus of global problem-solving”. Are cities capable of eliminating poverty and inequality, and of realizing children’s rights to thrive within their own boundaries, much less the rest of the world?

A: If these ambitious goals we have set on a global scale will be achieved anywhere, it will certainly be in cities. It is possible through infrastructure investment and better social policy and job creation to come very close to meeting the basic needs of the world’s urban population. This can make a big dent in global poverty, even if it does not reduce statistical inequality by much. It is in cities where we can best monitor whether children are benefiting from smart policies that aim to provide opportunities for the marginalized poor, such as in the cities of Brazil these days.

Q: Too many children in cities are denied such essentials as clean water, electricity and health care and become victims of exploitation. What can be done on the policy level to protect child rights in urban environments?

A: Protecting child rights in urban settings has to be connected to creating access to basic services. This unlocks the door to realizing the rights all children have. Investing in basic infrastructure and services is a win-win situation. It has been shown that countries that invest 8–10 per cent of GDP in infrastructure deliver higher long-term economic growth. From the government in Brazil to NGOs in India, we see very promising initiatives that are helping to fill the needs of marginalized urban families and their children in regards to health, education and nutrition. These are the models we should be promoting and spreading the most.

About Parag Khanna Parag Khanna is a Senior Research Fellow at the New America Foundation, Senior Fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations, Visiting Fellow at LSE IDEAS and Director of the Hybrid Reality Institute. He is author of Hybrid Reality: Preparing for the Age of Human-Technology Co-Evolution(2012), the international bestseller The Second World: Empires and Influence in the New Global Order (2008) and How to Run the World: Charting a Course to the Next Renaissance (2011). For more information visit his website: www.paragkhanna.com